Fact Sheets

For questions about our fact sheets, contact DPE at info@dpeaflcio.org.

Women Professionals: Making Gains Despite Persistent Inequality in the U.S. Workforce

2025 Fact Sheet

Highlights

More women than men are now earning advanced degrees and working in professional occupations, many which were once largely held exclusively by men. While some women are breaking the glass ceiling, many obstacles to attaining gender equality in the workplace still remain, especially in terms of pay.

In 2024, women made up 66 percent of union members in professional and related occupations. Nonunion women, including women professionals, are more likely than men to support unionization.

Smart public policy is needed to remedy the gender wage gap and address other gender inequality issues for working women. Guaranteed paid sick leave and paid family leave, more affordable and accessible childcare, and strengthened equal pay laws would go a long way to close the gender wage gap and build a stronger economy where American families feel supported.

Part I: Identifying Barriers

Women Professionals at Work

In 2024, women made up the majority, 52.3 percent, of workers in management, professional, and related occupations.[1] However, only 33 percent of chief executives are women,[2] and women only hold 9 percent of CEO positions at S&P 500 companies.[3]

Most mothers, even those with young children, participate in the labor force. In 2024, 68 percent of mothers with children under the age of six were in the workforce, and most of them worked full-time.[4] Among all mothers with children under 18, 74 percent were in the labor force, whereas among fathers with children under 18, 93.5 percent were in the labor force.[5]

Although women constitute the majority of professional employees and have gained greater representation over the past few decades in certain fields, including in legal occupations and in some scientific fields, their distribution in professional occupations skews toward administrative, education, and healthcare or caretaking roles. Meanwhile, women are still struggling to establish a foothold in male-dominated fields like engineering and computer science.

In 2024, women filled only 26.4 percent of computer and mathematical occupations, and 17.2 percent of architecture and engineering occupations.[6]

In comparison, women held 75.8 percent of healthcare practitioner and technical occupations and 73.4 percent of education, training, and library occupations in 2024.[7]

Educational Degrees of Women Professionals

Women have made significant strides in closing the education gap but remain underrepresented in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

Women have been earning more bachelor’s degrees than men since 1982 and they have been earning more master’s degrees than men since 1987.[8] Women received 57.9 percent of bachelor’s degrees and 61.9 percent of master’s degrees in the 2021–2022 academic year.[9]

The percentage of women enrolled in their first year of law school increased from 4.2 percent in 1963–64 to 56.1 percent in 2024.[10]

In 2024-2025, women made up 54.9 percent of all students enrolled in medical school.[11]

Even though women make up a majority of degree-holders from postsecondary institutions, high concentrations of either women or men in certain majors (and certain occupations) underscores the persistence of long-held assumptions about whether women or men are more likely to choose a particular major or career path.[12]

Women in STEM

Studies have shown that bias exists against women in STEM fields. Women have been disfavored in hiring decisions for lab positions, selection for mathematical tasks, evaluation of research abstracts for conferences, research citations, invitations to speak at symposia, postdoctoral employment and tenure decisions.[15]

A study found that there is “pervasive” discrimination towards female undergraduates in the science fields, finding that science professors in U.S. universities widely regard female undergraduates as less competent than their male counterparts with the same accomplishments and skills. The study also found that professors were less likely to offer women mentoring or employment, and if they were offered a job, the salary was lower.[16]

Another study found that male STEM professors are less likely to believe the body of evidence showing that systemic biases against women in STEM exist.[17]

While STEM jobs generally pay more than many other jobs, women in STEM are typically paid less than men in STEM.

Gender pay gaps exist among workers of varying races and ethnicities. Men in STEM who identify as Asian are typically among the highest earners, and women in STEM who identify as Black or Hispanic or Latina are typically among the lowest earners. These gaps are characteristic of inequalities found in other occupations too.[18]

The Gender Wage Gap Persists

The gender wage gap continues to plague the American workforce. In 2024, women in management, professional, and related occupations earned about $0.74 for every dollar earned by men. This represents a three-cent increase from twenty years prior, when women professionals earned about $0.71 for every dollar earned by men. The gap has persisted over the years, despite the fact that women have been earning the majority of college degrees.[19] Research has shown that work done by women is devalued much more often than work done by men.

A study analyzing Census data from 1950 through 2000 found that when the number of women in an occupation increases, the pay for those jobs decreases, even when controlling for education, work experience, skills, race and geography.[20]

The findings suggest that as more women go into historically male-dominated professions, the pay will drop.

For example, over the course of the twentieth century, as more women became professional designers, wages fell 34 percentage points, and as more women became biologists, wages fell 18 percentage points.[21]

The study also confirmed that the reverse was true – when an occupation “professionalized” and attracted more men, wages went up.

The masculinization of the computer programming field provides an example of this phenomenon. In the first half of the twentieth century, computer programmers (known as “computers”) were primarily women. While this work often involved knowledge of advanced computations, it was considered almost clerical in nature, and women were recruited for this work. Presently, men make up the vast majority of computer programmers (82.2 percent in 2024).[22] Their pay is much better than it was when computer programming was considered “women’s work.”[23]

Equal pay remains a problem in every occupational category. The average college educated woman loses almost $800,000 in wages over her lifetime.[24]

While women comprised 57 percent of workers in professional and related occupations in 2024, they earned 28 percent less than their male counterparts.[25]

In 2024, female elementary and middle school teachers earned 11.4 percent less than their male counterparts despite comprising 77 percent of the field.[26]

In 2024, female paralegals and legal assistants earned 18 percent less than their male counterparts despite comprising 81.3 percent of the field, and female lawyers earned 20 percent less than male lawyers.[27]

Women also earn less at every level of education. For full-time workers age 25 and older in 2023, women with a bachelor’s degree or higher earned $0.77 for every dollar earned by men with a comparable education.[28]

Additional Barriers for Working Women

Working women face other barriers that are not strictly related to pay. These obstacles can contribute to inequality in the workplace and can pose economic and health disadvantages to women.

Childcare Expenses

In the United States, childcare can be prohibitively expensive. In fact, it has become so expensive that it can push some families into poverty.[29] While the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has determined that the affordability benchmark for childcare is 7 percent of the family’s income, the Center for American Progress found that in 2023, “it would take 10 percent of median household income for two-parent households with children to afford the average national price of child care.”[30] That figure jumps to 32 percent for single-parent households.[31]

The high cost of childcare tends to force women out of the workforce. If a child needs to stay home from school or day care due to illness or other unforeseen circumstances, a parent might have to miss work to stay home and care for their child. Additionally, federal data has shown that “married mothers spend more time caring for children than married fathers, regardless of employment status.”[32] Women who leave the workforce to take care of children miss out on not only the salary they would have earned if they continued working but also wage growth – not to mention lost retirement assets and benefits. Working mothers were hit particularly hard during the COVID-19 pandemic, when parents had to juggle (unpaid) childcare responsibilities in addition to their regular job, all while navigating changing health and safety guidelines.[33]

In 2023, the average annual cost of full-time tuition and care for one infant at a childcare center was $14,019. The average annual cost for one four-year-old at a childcare center was $10,962.[34]

A 2023 study found that the U.S. childcare crisis costs the nation about $122 billion in lost earnings, productivity, and revenue annually.[35]

Inadequate Family Leave, Sick Leave, and Paid Time Off

Inadequate paid leave in the United States particularly hurts women, especially lack of paid leave after the birth of a child.

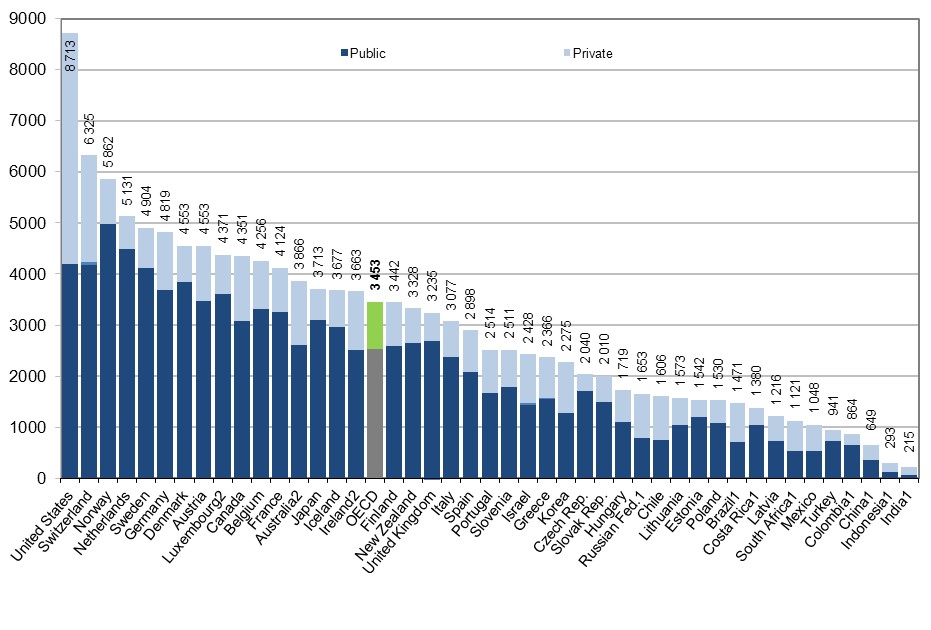

The United States is the only OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) country to not require paid leave for new parents. All other OECD countries require around two months of paid leave.[36]

A pivotal 2012 study found that women who used paid family leave were far more likely than those who did not to be working nine months to a year after their child was born, and women who took leave for 30 days or more were 54 percent more likely than women who did not take any leave to report wage increases in the year following their child’s birth.[37]

In 2024, about 34.4 million private-sector employees did not have paid sick time.[38]

Part II: Crafting Solutions

Women and the Union Advantage

On average, union members have higher pay and better benefits than non-union members. The wage gap between union men and women is narrower than the wage gap among non-union men and women. Joining or forming a union is a step women can take to increase wage equality.

In 2024, women union members made 87 percent of what men in unions made, while non-union women made 82 percent of what non-union male workers made.[39]

In 2024, union women earned weekly wages that were 21 percent more than non-union women.[40]

The median weekly earnings of union women who identified as Hispanic or Latina were 21 percent higher than their non-union counterparts.[43]

The union difference is apparent in the median hourly wages of predominantly female occupations. In 2024, for example, union preschool and kindergarten teachers earned 79 percent more than their nonunion counterparts. That year, union registered nurses earned 20 percent more than nonunion nurses.[44]

Union women and men are more likely than non-union workers to have health and pension benefits, and to receive paid holidays and vacations, and life and disability insurance.

In 2024, 9.5 percent of working women were union members.[45]

In 2024, among professional and related occupations, 10.3 percent were union members. Women made up 66 percent of union members in professional and related occupations.[46]

Surveys have found that women, including women professionals, are more likely to support unionization than men. Additionally, in union organizing elections, majority-female occupations have consistently shown much higher win rates than organizing drives in industries with fewer women members.[47]

Public Policy

Smart public policy is needed to remedy the gender wage gap and address other gender inequality issues for working women.

Guarantee Paid Sick Leave

Paid sick days can prevent workers from putting their families’ health and financial security at risk when someone in the family is sick. Paid sick leave can also reduce the spread of contagious illnesses by enabling working people to stay home when they don’t feel well. It can also decrease health care costs by reducing the likelihood of emergency room visits.[48]

The vast majority of voters support paid sick days for workers.[49]

Mandate Paid Family Leave

The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) is a federal law that provides employees with job protection if they need to take time off for qualified family or medical reasons; however, the law does not guarantee that the time off is paid.

Fourteen states and the District of Columbia have passed laws creating paid family and medical leave programs.[50]

About 73 percent of private sector employees do not have access to paid family leave.[51]

Working women are hit hardest by the lack of paid family leave because they continue to take on the majority of unpaid family care work.[52]

Make Child Care Affordable

While subsidies exist through federal and state funding streams to assist low-income families with the cost of child care, the funds are insufficient to adequately address the child care needs of low- and middle-income families.

More federal subsidies and increased access to subsidies would mean that more parents, especially mothers, would be able to participate in the workforce, more children would gain access to high-quality education, and more employers would be able to maintain their workforce, leading to a healthier economy.[53]

Strengthen Equal Pay Laws

The Equal Pay Act, signed in 1963, requires men and women to be paid equally for equal work. However, over time, the Equal Pay Act’s protections have been weakened; namely, the courts’ broad interpretation of employers’ defenses outlined in law has made it easier for employers to claim that employees received different pay for a reason other than sex, allowing them to avoid liability for sex discrimination. Also, the Equal Pay Act does not specifically address pay transparency or pay secrecy.[54]

The Paycheck Fairness Act, which has been introduced multiple times in Congress, would strengthen the Equal Pay Act.[55]

Conclusion

Although women make up more than half of the professional labor force, they still do not receive the same treatment and opportunities as men. The persistence of a gender wage gap impacts almost every aspect of women’s lives in the United States. The work of labor unions, fighting for better wages and benefits, makes a huge difference for working women and should be part of the solution to close the wage gap and achieve equality in the workplace. Additionally, public policies that empower women to work and pursue careers that interest them and pay them fairly are an important part of a comprehensive solution to gender inequality in the U.S. workforce.

For more information on professional and technical workers, see DPE’s website: www.dpeaflcio.org.

[1] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table 11. Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. 2024.” (January 29, 2025). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Hinchliffe, Emma and Joey Abrams. “S&P 500 boards have hit a tipping point that may lead to more female CEOs.” (March 25, 2024). Fortune. Retrieved from https://fortune.com/2024/03/25/female-women-ceos-diverse-boards-sp-500/.

[4] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table 5. Employment status of the population by sex, marital status, and presence and age of own children under 18, 2023-2024 annual averages.” (April 23, 2025). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/famee.t05.htm.

[5] Ibid.

[6] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table 11.” [above, n. 1].

[7] Ibid.

[8] U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, Table 310, “Degrees conferred by degree-granting institutions, by level of degree and sex of student: Selected years, 1869-70 through 2021-22.” Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d12/tables/dt12_310.asp.

[9] Ibid.

[10] American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar. “Enrollment and Degrees Awarded, 1963-2012 Academic Years.” Retrieved from

www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/statistics/enrollment_degrees_awarded.pdf; and American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar. “2024 Standard 509 Information Report Data Overview.”(December 16, 2024). Retrieved from https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/statistics/2024/2024-standard-509-information-report-data-overview.pdf.

[11] “New AAMC Data on Medical School Applicants and Enrollment in 2024.” (January 9, 2025). Association of American Medical Colleges. Retrieved from https://www.aamc.org/news/press-releases/new-aamc-data-medical-school-applicants-and-enrollment-2024.

[12] Kochhar, Rakesh. “The Enduring Grip of the Gender Pay Gap.” (March 1, 2023). Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/03/01/the-enduring-grip-of-the-gender-pay-gap/.

[13] U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics. “Table 325.40. Degrees in education conferred by postsecondary institutions, by level of degree and sex of student: Selected academic years, 1949-50 through 2021-22.” Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/current_tables.asp.

[14] U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics. “Table 325.45. Degrees in engineering and engineering technologies conferred by postsecondary institutions, by level of degree and sex of student: Selected academic years, 1949-50 through 2020-21.” Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/current_tables.asp.

[15] Handley, Ian M., Elizabeth R. Brown, Corinne A. Moss-Racusin, and Jessi L. Smith. “Quality of evidence revealing subtle gender biases in science is in the eye of the beholder.” (October 27, 2015). The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), 112, 43, pp. 13201–13206. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.1510649112.

[16] Chang, Kenneth. “Bias Persists for Women of Science, a Study Finds.” (September 24, 2012). The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/25/science/bias-persists-against-women-of-science-a-study-says.html.

[17] Cook, Lindsey. "More Depressing News for Women in STEM." U.S. News and World Report, January 6, 2016. http://www.usnews.com/news/blogs/data-mine/articles/2016-01-06/researchers-show-male-stem-faculty-less-likely-to-support-research-showing-gender-bias.

[18] Fry, Richard, Brian Kennedy and Cary Funk. “STEM Jobs See Uneven Progress in Increasing Gender, Racial and Ethnic Diversity.” (April 1, 2021). Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2021/04/01/stem-jobs-see-uneven-progress-in-increasing-gender-racial-and-ethnic-diversity/.

[19] U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics. Table 310. [above, n. 8].

[20] Miller, Claire Cain. “As Women Take Over a Male-Dominated Field, the Pay Drops.” (March 18, 2016). The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/20/upshot/as-women-take-over-a-male-dominated-field-the-pay-drops.html.

[21] Ibid.

[22] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table 11.” [above, n. 1].

[23] See, e.g., Janet Abbate, Recoding Gender: Women’s Changing Participation in Computing (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press), 2012; and Nathan Ensmenger, The Computer Boys Take Over: Computers, Programmers, and the Politics of Professional Expertise (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press), 2010.

[24] Gould, Elise, Jessica Schieder, and Kathleen Geier. “What is the gender pay gap and is it real?: The complete guide to how women are paid less than men and why it can’t be explained away.” (October 20, 2016). Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.epi.org/publication/what-is-the-gender-pay-gap-and-is-it-real/.

[25] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table 11,” [above, n. 1]; and U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table 39: Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by detailed occupation and sex, 2024.” (January 29, 2025). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat39.htm.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table 14: Women's earnings as a percentage of men’s, by educational attainment, for full-time wage and salary workers 25 years and older, 1979–2023.” In “Highlights of women’s earnings in 2023.” (August 2024). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-earnings/2023/home.htm.

[29] Ross, Kyle and Kennedy Andara. “Child Care Expenses Push an Estimated 134,000 Families Into Poverty Each Year.” (October 31, 2024). Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/child-care-expenses-push-an-estimated-134000-families-into-poverty-each-year/.

[30] Schneider, Allie. “A 2024 Review of Child Care and Early Learning in the United States.” (January 30, 2025). Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/a-2024-review-of-child-care-and-early-learning-in-the-united-states/.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Johnson, Richard W., Karen E. Smith, and Barbara Butrica. “Unpaid Family Care Continues to Suppress Women’s Earnings.” (June 9, 2023). Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/unpaid-family-care-continues-suppress-womens-earnings.

[33] See, e.g., Schneider, “A 2024 Review of Child Care and Early Learning in the United States,” [above, n. 30]; and Katherine Gallagher Robbins and Jessica Mason, “Women’s unpaid caregiving is worth more than $625 billion – and it could cost more,” (August 14, 2023), National Partnership for Women and Families. Retrieved from https://nationalpartnership.org/womens-unpaid-caregiving-worth-more-than-625-billion/.

[34] “Data on Child Care and Early Learning in the United States.” (2024). Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/data-view/early-learning-in-the-united-states/.

[35] Bishop, Sandra. “$122 Billion: The Growing, Annual Cost of the Infant-Toddler Child Care Crisis.” (February 2023). ReadyNation. Retrieved from https://www.strongnation.org/articles/2038-122-billion-the-growing-annual-cost-of-the-infant-toddler-child-care-crisis.

[36] Livingston, Gretchen and Deja Thomas. “Among 41 nations, U.S. is the outlier when it comes to paid parental leave.” Pew Research Center. (December 16, 2019). Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/09/26/u-s-lacks-mandated-paid-parental-leave/.

[37] Houser, Linda and Thomas P. Vartanian. “Pay Matters: The Positive Economic Impacts of Paid Family Leave for Families, Businesses and the Public.” (January 2012). Center for Women and Work, Rutgers University. Retrieved from https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/pay-matters.pdf.

[38] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table 6. Selected paid leave benefits: Access, March 2024.” (September 19, 2024). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/ebs2.t06.htm.

[39] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table 41. Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by union affiliation and selected characteristics.” (January 29, 2025). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat41.htm.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey Microdata. 2024. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/mdat.

[45] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table 40. Union affiliation of employed wage and salary workers by selected characteristics.” (January 29, 2025). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat40.htm.

[46] U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey Microdata. 2024. [above, n. 43].

[47] Bronfenbrenner, Kate and Robert Hickey, “Changing to Organize: A National Assessment of Union Organizing Strategies,” in Ruth Milkman and Kim Voss, eds., Organize or Die: Labor’s Prospects in Neoliberal America, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004); Kate Bronfenbrenner, “Organizing Women: The Nature and Process of Union Organizing Efforts among U.S. Women Workers since around the Mid-1990’s,” Work and Occupations, 32, 4, November 2005.

[48] “Fact Sheet: The Healthy Families Act.” (November 2023). National Partnership for Women and Families. Retrieved from https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/the-healthy-families-act-fact-sheet.pdf.

[49] Ibid.

[50] “Chart: State Paid Family & Medical Leave Insurance Laws.” (July 2024). National Partnership for Women and Families. Retrieved from https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/state-paid-family-leave-laws.pdf.

[51] Williamson, Molly Weston. “The State of Paid Family and Medical Leave in the U.S. in 2024.” (January 17, 2024). Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-state-of-paid-family-and-medical-leave-in-the-u-s-in-2024/.

[52] “Fact Sheet: Legislative Proposals for Updating the Family and Medical Leave Act.” (February 2020). National Partnership for Women and Families. Retrieved from https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/updating-the-fmla.pdf.

[53] Giannarelli, Linda, Gina Adams, Sarah Minton, and Kelly Dwyer. “What If We Expanded Child Care Subsidies?” (June 2019). Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/100284/what_if_we_expanded_child_care_subsidies_5.pdf.

[54] Holmes, Kaitlin, Jocelyn Frye, Sarah Jane Glynn, and Jessica Quinter. “Rhetoric vs. Reality: Equal Pay.” Center for American Progress. (November 7, 2016). Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2016/11/07/292175/rhetoric-vs-reality-equal-pay/.

[55] “Fact Sheet: The Paycheck Fairness Act.” (March 2023). National Partnership for Women and Families. Retrieved from https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/the-paycheck-fairness-act.pdf.

Library Professionals: Facts & Figures

2025 Fact Sheet

Highlights:

In 2024, employment among librarians increased more than 27 percent, while employment among library assistants declined and library technicians remained steady. More research is needed to determine the cause of the sharp increase in librarians from 2023 to 2024.

In 2024, librarians who were union members earned on average almost 41 percent more per week than their non-union counterparts. Union library professionals are more likely than their non-union counterparts to be covered by a retirement plan, health insurance, and paid sick leave.

The librarian profession suffers from a persistent lack of racial and ethnic diversity that has not changed significantly over the past two decades. Librarians and other library professionals also tend to be slightly older than the general workforce.

Librarians and other library professionals provide essential services for schools, universities, and communities. Americans go to libraries for free, reliable, and well-organized access to books, the Internet, and other sources of information and entertainment. They rely on library personnel for help with research and reference questions and searches for employment and government assistance, among other things. And they take part in programs for children, immigrants, seniors and other groups with specific needs and interests.

This fact sheet explores the role of library staff in the workforce, the demographics, educational attainment and wages of librarians, as well as the benefits of union membership for library professionals.

Library Occupations and Library Usage: By the Numbers

Library Employment

In 2024, there were approximately 289,400 professional and technical workers employed in libraries in the United States, including 186,500 librarians, 37,400 library technicians, and 65,500 library assistants. They worked in public libraries, primary and secondary schools, institutions of higher education, museums and archives, as well as in libraries operated by private corporations, government agencies, and other organizations.

Employment of library professionals has been gradually declining after hitting a peak of almost 395,000 in 2006, though the most recent figures suggest that the number of employed librarians has returned to pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels.[1] There was a relatively sharp increase in the number of librarians from 2023 to 2024. It is possible that grants awarded to libraries and institutions enabled the hiring of more library professionals during this period, though more research is needed to determine what factors may have caused the abrupt increase.

Library Programs

In fiscal year 2022, more than 17,500 U.S. public libraries circulated about 2.2 billion print and electronic materials and offered 3.3 million programs, attended by about 64 million members of the public. Children’s programs accounted for 49 percent of all programs offered, serving over 35 million children and parents.[2]

Electronic media, computer use and internet access are an increasing component of library materials and services, and e-books now comprise 57 percent of all collection materials. In addition, library patrons accessed over 273,000 public computers over 83 million times during fiscal year 2022.[3]

Libraries provide important training and educational programs for the public. A 2020 survey by the Public Library Association revealed that more than 88 percent of public libraries offer at least basic digital literacy training, and in many cases more advanced technology training.[4] Additionally, a 2022 survey also by the Public Library Association revealed that 78 percent of public libraries provide job and career services; 24 percent have workforce development programs; and 51 percent offer assistance with health insurance enrollment.[5]

A 2023 study published by the American Library Association (ALA) found that 54 percent of Gen Z (born 1997-2012) and Millennials visited a physical library within the past year.[6]

Duties and Roles of Library Professionals

While specific roles and responsibilities may change depending on the size and setting of libraries, librarians and other library professionals’ main role is to help people find information and conduct research on a variety of personal, professional, and academic subjects. Library professionals also teach classes, organize library collections, and tailor programs to a variety of audiences, including young children, students, professionals, and the elderly.[7]

Librarians are also often responsible for multiple aspects of management, including ordering books and other materials; purchasing new technology; supervising library technicians, assistants, and volunteers; and managing library budgets.[8]

Library technicians assist librarians in the operation of libraries, and their tasks include assisting visitors, organizing library materials, and performing administrative and clerical functions. Library assistants have similar roles as library technicians, but may have fewer independent responsibilities.[9]

Where Library Professionals Work

Librarian employment in 2024 was split between public libraries (27 percent); elementary and secondary schools (34 percent); colleges, universities, and professional schools (22 percent); and other libraries and archives, including those at law firms, nonprofit organizations, and scientific organizations (17 percent).[10]

Employment of library technicians in 2024 was split between public libraries (60 percent); elementary and secondary schools (10 percent); colleges, universities, and professional schools (18 percent); and other libraries and archives in the private sector (12 percent).

Employment of library assistants in 2024 was split between public libraries (48 percent); colleges, universities, and professional schools (19 percent); elementary and secondary schools (14 percent); and other libraries and archives, including those at businesses and scientific organizations (19 percent).[11]

In 2024, 20 percent of librarians, 52 percent of library technicians, and 54 percent of library assistants worked part-time.[12]

Racial and Ethnic Diversity and Age Demographics of Library Professionals

The librarian profession suffers from a persistent lack of racial and ethnic diversity that has not changed significantly over the past two decades.[13]

Librarians were slightly less diverse than the workforce of professionals in all education, training, and library occupations, which was almost 79 percent white in 2024. Black and African American professionals made up 11 percent of the total education, training, and library workforce, while Hispanic and Asian professionals represented 12.6 percent and 6.5 percent, respectively.[14]

In 2024, a little less than seven percent of librarians identified as Black or African American and 13 percent identified as Hispanic or Latino of any race. Additionally, librarians identifying as Asian American or Pacific Islander made up only 4 percent.[15]

In 2024, just over 84 percent of librarians and 71 percent of library assistants identified as white.[16]

Librarians and other library professionals skew older than the general workforce. While Americans over 55 accounted for 23 percent of the total workforce in 2024, 34 percent of librarians were over the age of 55.[17]

Educational Attainment

In many settings, librarians are required to hold at least a master’s degree in library science or meet state teaching license standards for being a school librarian.[18] Many other library workers, including lower-paid library technicians and library assistants have high educational attainment as well.

In 2024, 54 percent of librarians held a master’s degree or higher, 26 percent held a bachelor’s degree, and 5 percent held an associate’s degree.[19]

In comparison, in 2024, 8 percent of library technicians held a master’s degree or higher, 30 percent held a bachelor’s degree, 10 percent held an associate’s degree, and 47 percent had a high school diploma or equivalent as their highest degree attained.

In 2024, 21 percent of library assistants held a master’s degree or higher, 33 percent held a bachelor’s degree, 7 percent held an associate’s degree, and 14 percent had a high school diploma or equivalent as their highest degree attained.[20]

Women and Library Professions

In 2024, women accounted for 89.2 percent of all librarians, an increase of 6.7 percentage points from the year prior. Women accounted for 84.2 percent of library assistants, which was above the average of 73.4 percent for women employed in all education and library professions.[21]

Women represented 82.5 percent of graduates in Master of Library Science (MLS) programs in 2021-2022. However, Black women and Asian or Pacific Islander women only accounted for 4.6 percent and 2.7 percent of all MLS graduates, respectively. Hispanic women made up 8.4 percent of the 2022 class.[22]

Library Worker Earnings and the Wage Gap

In 2024, the mean hourly wage for librarians working full-time was $33.26 and the mean annual salary was $69,180. The mean hourly wage for library technicians was $20.70, and $18.22 for library assistants.[23]

Regional Variance in Salaries

Librarian earnings vary significantly from region to region. The District of Columbia had the highest mean annual earnings for full-time librarians at $94,300 in 2024, followed by Washington, California, Maryland, and New York. These salaries were not adjusted for differences in cost of living across states.[24]

Institutional Variance in Compensation

Library staff compensation also varied based on the type of library employer. On average, in 2024, librarians working full-time at elementary and secondary schools earned $69,880, those working at public colleges, universities, and professional schools earned $68,570, and those employed by local governments (excluding education) made $60,510.[25]

Gender Inequality

Pay inequity remains a persistent and pervasive problem in society. In 2024, median weekly earnings for women in all occupations were 82.7 percent of men’s earnings.[26] For most women of color, the earnings gap is even larger: Black or African American women earned just 73 cents for every dollar earned by men of all races in 2024, and Hispanic or Latina women earned just 66 cents on the dollar.[27] Asian women were the only racial group to earn more than men of all races, but they still earned only 79 cents to the dollar reported by Asian men.[28]

Though library occupations are predominantly held by women, a wage gap still exists in the profession. Even though the wage gap for librarians has narrowed considerably in recent years – from 88 percent of the median annual earnings reported by men in 2021 to 97.7 percent in 2022 – that figure went back down to 91.1 percent in 2023.[29] In 2023, women working as full-time library assistants reported median annual earnings that were 94.3 percent of the median annual earnings reported by men.[30]

The 6th edition of the American Library Association-Allied Professional Association’s Advocating for Better Salaries Toolkit includes sections on how to determine fair compensation for librarians, advocate for raises, identify pay inequities, and negotiate salaries. Importantly, the toolkit identifies union organizing and collective bargaining as an effective means to increase librarian pay and increase equity in the workplace.[31]

Health Benefits

In 2023, 79.4 percent of librarians had health insurance through a current or former employer or union, though librarians working 35 hours per week or more had a much higher coverage rate of 91.6 percent. In 2023, 2.7 percent of librarians did not have health insurance coverage.[32]

Among library technicians in 2023, just 65 percent received health insurance through a current or former employer or union, though library technicians working 35 hours per week or more had a higher coverage rate of 83.5 percent. A total of 8 percent were uninsured that year, up from 3.6 percent who were uninsured the year prior.[33]

Among library assistants in 2023, 63 percent had employer-provided health insurance, though the rate was higher for full-time library assistants at 84 percent, leaving 5.4 percent of library assistants uninsured in 2023.[34]

The Union Difference

Unions are an important way for library professionals to negotiate collectively for better pay, benefits, and working conditions. Unions work to elevate library professions and secure working conditions that make it possible to provide quality service.

In 2024, professionals working in education, training, and library occupations had the highest unionization rate for any occupation group, 35.8 percent.[35]

In 2024, 24.6 percent of librarians were union members.[36]

Wages and Benefits

Union librarians and library workers have leveraged their collective voices to earn fair wages and stronger benefits. Wages and benefits earned by union librarians and library workers are more commensurate with the skilled and professional nature of library work.

In 2024, librarians who were union members earned on average almost 41 percent more per week than their non-union counterparts and union library technicians earned 12 percent more per week than their non-union counterparts.[37] While these statistics are subject to volatility due to small sample sizes, trends in the data show that it pays to be a union library professional.

Union members are more likely than their non-union counterparts to be covered by a retirement plan, health insurance, and paid sick leave. In 2024, 95 percent of union members in the civilian workforce had access to a retirement plan, compared with only 72 percent of non-union workers. Similarly, 95 percent of union members had access to employer provided health insurance, compared to 71 percent of non-union workers. Additionally, 91 percent of union members in the civilian workforce had access to paid sick leave compared to 79 percent of non-union workers.[38]

Union Library Professionals Success Stories

In many states, collective bargaining rights of public sector employees, including professionals at public libraries, are established by state and municipal laws rather than at the federal level. This creates additional barriers for public sector workers to join together in union. While some states have anti-union laws in place that restrict the extent to which public sector employees can collectively bargain, that trend has been changing over the last few years, as some states have passed pro-worker legislation. Featured below are some legislative and organizing highlights from union library professionals over the past few years.

In late April 2024, library professionals in the state of Maryland won collective bargaining rights when the state’s Library Workers Empowerment Act was signed into law. Before this law existed, the right of library professionals to collectively bargain in this state was determined on a county-by-county basis. Library professionals across Maryland will now be able to collectively negotiate with their employers for better pay and benefits and improved working conditions through union representation. Additionally, in 2022, after fighting for years for their right to collectively bargain in Baltimore County, Maryland, public library employees voted to unionize and join the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAM).[39] The IAM worked with Maryland public library employees to help advocate for the collective bargaining rights of library workers and the passage of the 2024 Library Workers Empowerment Act.

Advocacy for public sector collective bargaining has also been gaining momentum in the state of Virginia over the past few years, as a growing number of counties and municipalities have been passing laws granting collective bargaining rights to more public sector employees, including public library workers.[40] This activity is due to a state law that went into effect in May 2021 allowing counties, municipalities, and towns to recognize labor unions as bargaining representatives for public employees. A major victory for Virginia’s public sector professionals in education and library services took place in June 2024, when over 27,000 public sector school employees, including school librarians, in Virginia’s Fairfax County voted overwhelmingly to join in union and be represented jointly by the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the National Education Association.[41]

Additionally, in March 2023, the state of Michigan repealed its anti-union right-to-work law, which allowed employees in unionized workplaces to opt out of paying dues while still reaping the benefits of union representation. When the law went into effect in February 2024, Michigan’s union library professionals – and unionized employees more broadly – became part of stronger unions that are now better able to support the needs of their members.

Gains made by union library professionals in their first contracts

Library professionals have seen organizing victories and contract gains across the U.S. Unions including AFT, IAM, Office and Professional Employees International Union (OPEIU), and the United Steelworkers (USW) represent a growing number of library professionals in both public and private sector libraries. Many union library professionals who have recently ratified their first contracts have seen significant gains, including increases in pay and starting salaries, guaranteed annual wage increases, and greater job protections.

In January 2024, library professionals and library workers represented by the Ohio Federation of Teachers (part of AFT) at the Grandview Heights Public Library in Grandview Heights, Ohio ratified their first contract. They won new benefits of paid parental leave and partial tuition reimbursement, as well as 12 percent raises over the course of the contract.[42]

In June 2023, college staff, including library professionals, represented by OPEIU at the Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle, Washington ratified their first contract, which included a retroactive base wage increase of four percent to the previous year and an additional three percent wage increase in the first year of the contract. They also secured protective measures against layoffs in the event of the introduction of new technology that could impact staffing, and the agreement established a Labor Management Committee to promote improved working conditions.[43]

In July 2022, librarians, archivists, and curators across all three University of Michigan campuses ratified their first contract after voting the previous year to join in union with AFT Local 6244, the Lecturers’ Employee Organization. Among other substantial gains, the librarians, archivists, and curators on the lowest end of the pay scale received raises between nine and 30 percent. Additionally, collective bargaining granted academic freedom to these library professionals, a right previously afforded only to university faculty.[44]

In January 2022, library professionals represented by USW at the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh ratified their first contract, which included “standardizing positions into ‘Job Grades’ and increasing starting wages, most significantly among the lowest-paid positions; wage increases for current workers guaranteed by four raises over the life of the four-year agreement; limitations to health insurance rate hikes, and the addition of Christmas Eve and Juneteenth as paid holidays.”[45]

[1] U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey Microdata. 2024. Available at https://data.census.gov/app/mdat/.

[2] The Institute of Museum and Library Services. PLS Benchmarking Tables. Fiscal year 2022. Available at https://www.imls.gov/pls-benchmarking-tables. The most recent data that is publicly available on the Public Library Survey is from fiscal year 2022.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Public Library Association. (2021). 2020 Public Library Technology Survey Summary Report. Available at https://alair.ala.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/92286029-0155-4aed-aca9-47a187140466/content.

[5] Public Library Association. (2023). Public Library Services for Strong Communities Report: Results from the 2022 PLA Annual Survey. Available at https://www.ala.org/sites/default/files/pla/content/data/PLA_Services_Survey_Report_2023.pdf

[6] Berens, Kathi Inman and Rachel Noorda. (2023). “Gen Z and Millennials: How They Use Public Libraries and Identify Through Media Use.” American Library Association. Available at https://www.ala.org/sites/default/files/advocacy/content/tools/Gen-Z-and-Millennials-Report%20%281%29.pdf.

[7] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Outlook Handbook, “Librarians and Library Media Specialists.” 2024. Available at https://www.bls.gov/ooh/education-training-and-library/librarians.htm

[8] Ibid.

[9] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Outlook Handbook, Library Technicians and Assistants.” 2024. Available at https://www.bls.gov/ooh/education-training-and-library/library-technicians-and-assistants.htm

[10] U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey Microdata. 2024. [above, n. 1]. For the purposes of this factsheet, all private sector libraries and archives are included in the “other private and nonprofit libraries” classification, though some private, not-for-profit libraries (such as the Carnegie system of libraries in Pittsburgh) play the role of public libraries in their communities.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] In comparison, librarians were 85 percent white in 2015, 84 percent white in 2010 and 88 percent white in 2005. Source: U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey Microdata. 2005-2015. Available at https://data.census.gov/app/mdat/.

[14] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Table 11: Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, Annual Averages, 2024. Available at https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.pdf.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Table 11b: Employed persons by detailed occupation and age, 2024. Available at https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11b.htm.

[18] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Outlook Handbook, “Librarians.” [above, n. 7].

[19] U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey Microdata. 2024. [above, n. 1].

[20] Ibid.

[21] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Table 11: Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, Annual Averages, 2024. Available at https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.pdf.

[22] U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics. Tables 323.30 and 323.50. 2021-2022. Available at https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/2023menu_tables.asp. The most recent data that is publicly available about MLS graduates from the National Center for Education Statistics’ is from 2021-2022.

[23] Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics. Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2024. Available at https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_stru.htm.

[24] Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics. Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2024 OEWS Profiles. Available at https://data.bls.gov/oesprofile/.

[25] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Outlook Handbook, “Librarians.” [above, n. 7]

[26] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey, Table 37, “Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by selected characteristics.” 2024. Available at http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat37.pdf.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] U.S. Census Bureau. Full-Time, Year-Round Workers & Median Earnings by Sex & Occupation. American Community Survey. 2023. Available at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/industry-occupation/median-earnings.html..

[30] Ibid.

[31] Bartholomew, Amy, Jennifer Dorning, Julia Eisenstein, & Shannon Farrell. “Advocating for Better Salaries Toolkit.” ALA Allied Professional Association. April 2017. Available at https://alair.ala.org/items/4c36b254-8692-41e7-bcb2-d570b4cc4498

[32] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata, 2023. Available at https://data.census.gov/app/mdat/.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 42. Union affiliation of employed wage and salary workers by occupation and industry.” 2024. Available at https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat42.htm

[36] Hirsch, Barry and Macpherson, David. Union Membership, Coverage, Density, and Employment by Occupation, 2024. Union Membership and Coverage Database from the CPS. Available at http://unionstats.com/

[37] U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey Microdata. 2024. [above, n. 1].

[38] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2024. Available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ebs2.pdf.

[39] DeVille, Taylor. “Baltimore County Library Staff Votes to Form Union.” Baltimore Sun. January 7, 2022. Available at https://www.baltimoresun.com/maryland/baltimore-county/bs-md-co-county-library-staff-unionize-20220107-unnyd7xavvbsrcj3amgwda7fry-story.html.

[40] Overman, Stephenie. “In Virginia, ‘Patchwork’ of Ordinances Makes Public-Sector Organizing a Maze.” Virginia Mercury. January 16, 2023. Available at https://virginiamercury.com/2023/01/16/in-virginia-patchwork-of-ordinances-makes-public-sector-organizing-a-maze/.

[41] “More than 27,500 Fairfax County (Va.) Education Workers Overwhelmingly Win Historic Union Elections.” American Federation of Teachers. June 10, 2024. Available at https://www.aft.org/press-release/more-27500-fairfax-county-va-education-workers-overwhelmingly-win-historic-union.

[42] “First Union Contract Goes Into Effect for Grandview Heights Public Library Workers.” Ohio Federation of Teachers, AFT. January 2, 2024. Available at https://www.oft-aft.org/press/first-union-contract-goes-effect-grandview-heights-public-library-workers.

[43] Collective Bargaining Agreement Between the Cornish College of the Arts and Office and Professional Employees International Union Local no. 8, AFL-CIO, For the period of July 25, 2023 through August 31, 2025. Available at https://www.cornish.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Cornish-CBA-OPEIU8-_2023-2025.pdf.

[44] Dodge, Samuel. “17% Salary Increase Part of First-ever Librarian Union Deal with University of Michigan.” Michigan Live. July 29, 2022. Available at https://www.mlive.com/news/ann-arbor/2022/07/17-salary-increase-part-of-first-ever-librarian-union-deal-with-university-of-michigan.html.

[45] “Carnegie Library Workers Ratify First Labor Agreement.” United Steelworkers. January 7, 2022. Available at https://m.usw.org/news/media-center/releases/2022/carnegie-library-workers-ratify-first-labor-agreement.

Use and Abuse of the J-1 Exchange Visitor Teacher Program

2025 FACT SHEET

Highlights

Public and private schools use the J-1 exchange visitor teacher program to employ teachers from abroad in the United States. Despite facilitating employment, the J-1 visa program lacks the appropriate safeguards to prevent workplace abuse, harming J-1 teachers and U.S. educators alike.

The U.S. Department of State, which oversees this employment program, provides very little oversight over employer recruitment practices and J-1 teachers’ working conditions. Additionally, publicly available data about the J-1 teacher program is limited.

Reforms are needed to ensure that there is adequate regulatory oversight over the J-1 visa program and its teacher recruitment practices. The U.S. Department of Labor should have an oversight role, J-1 teachers must be informed of their workplace rights, and more transparency is needed about schools’ use of the J-1 teacher program.

DPE supports reforming the J-1 exchange visitor program based on the experiences of union professionals. The more than four million members of DPE’s 24 affiliated unions include U.S. citizens, permanent residents, and people working on nonimmigrant visas, including the J-1 visa. Employers routinely use the J-1 exchange visitor program, including the teacher program, to take advantage of the program’s lack of safeguards. Reform is needed to ensure that J-1 programs with an employment component are regulated as work visa programs.

The J-1 Exchange Visitor Teacher Program: History and Eligibility

The J-1 exchange visitor teacher program allows accredited public and private schools to bring teachers from abroad to work full-time in the United States. This visitor teacher program is one of several categories in the J-1 exchange visitor program, a nonimmigrant visa program that permits people from other countries to temporarily work or study in the United States. While Congress established the J-1 program to promote cultural exchange and strengthen diplomatic ties between the United States and other countries, most people enter the United States on J-1 visas to work.[1]

A school may hire someone through the J-1 teacher program if that person meets the qualifications for teaching at the pre-K or K-12 levels in their home country and if they have at minimum a degree equivalent to a U.S. bachelor’s degree in either education or the subject in which they intend to teach.[2]

J-1 visas for teachers are valid for an initial three years, and they may be renewed for up to two additional years.[3] Schools may hire returning J-1 teachers if they have resided outside of the U.S. for at least two years and continue to meet the program’s eligibility requirements.[4]

Few Regulations Govern the J-1 Teacher Program

The U.S. Department of State (hereafter State Department), which oversees the J-1 exchange visitor program, provides very little oversight of the recruitment practices and working conditions faced by J-1 teachers.[5] While employment is a core component of the J-1 teacher visa, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) has no formal oversight role. Despite facilitating employment, the J-1 visa program lacks the appropriate safeguards to prevent workplace abuse, harming J-1 teachers and U.S. educators alike.

Typically, teachers in other countries learn about the J-1 teacher program and apply to work in the U.S. through unregulated labor recruitment agencies. Unlike work visa programs governed by DOL regulations, agencies recruiting for the J-1 teacher program are allowed to charge recruitment fees and other expenses, which can amount to tens of thousands of dollars.[6] J-1 teachers typically cannot pay this total upfront, leaving them saddled with high-interest debt owed to their recruiters before they even arrive in the U.S. and start teaching.[7] According to a 2014 study by Education International, “recruiting agencies commonly earn between $5,000 and $20,000 for each teacher they place in a U.S. teaching position, with fees being collected from teachers or school districts, and in some cases, both.”[8] This profit-driven business model, coupled with unregulated recruitment practices, underscores the predatory nature of many of these agencies.

Contrary to comparable temporary work visa programs, the uncapped J-1 teacher program has no specific wage regulations other than the requirement that positions must “comply with any applicable collective bargaining agreement.”[9] Therefore, absent a union contract, employers may elect to pay J-1 teachers significantly less than they pay other teachers working in the same school. Lacking even the bare minimum protections of work visa programs, school systems that employ J-1 teachers do not need to seek any type of pre-approval or labor certification from the DOL. Employers, in most cases, are not required to pay federal FICA taxes for J-1 employees, providing a strong financial incentive for schools to skip past available, qualified U.S. educators.[10]

Quantifying the J-1 Exchange Visitor Teacher Program

Source: Compiled from “Facts and Figures: BridgeUSA J-1 Visa Basics,” U.S. Department of State (see footnote 11 for citation).

The State Department does not release substantive data about who is employed through the J-1 teacher program, what they are paid, and in what schools the J-1 teachers work. The limited public data makes clear that K-12 school systems are increasing their use of the J-1 teacher program to recruit teachers. However, we do not know the ages, genders, or countries of origin of J-1 teachers nor the specific public or private schools that employ them. The chart below shows the number of J-1 teacher program participants in the United States from 2016 to 2023. With the exception of 2020, when there was a sharp drop in the number of J-1 teachers in the country due to travel and nonimmigrant visa restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of J-1 teachers steadily increased during this period such that by 2023, the number of J-1 teachers in the United States was 154 percent greater than in 2016.[11]

The lack of detailed program data makes it difficult to understand the degree to which specific school districts are relying on the J-1 teacher program and its impact on the overall labor market conditions for educators; however, the State Department has periodically reported on the number of J-1 teachers at the state level. Indeed, some states disproportionately rely on the J-1 teacher program. Between 2016 and 2023, six states – North Carolina, Texas, Florida, South Carolina, Arizona, and California – had over 2,000 J-1 teachers working in U.S. schools. North Carolina schools employed the most J-1 teachers, with over 4,800 working in the state between 2016 and 2023.

Workplace Rights for J-1 Teachers

Source: Compiled from “Facts and Figures: BridgeUSA J-1 Visa Basics,” U.S. Department of State

J-1 teachers working in unionized schools have the right to become members of and fully participate in their unions, and are protected by applicable labor law. J-1 teachers working in public schools are protected by state public sector labor law, while those working in private or charter schools are fully protected by the National Labor Relations Act, including having the right to participate in efforts to organize new unions at their workplaces. Additionally, J-1 visa program regulations clearly state that program sponsors and employers are not allowed to retaliate against J-1 visa program participants for consulting with advocacy, community, and legal organizations, filing complaints against sponsors and employers, testifying in proceedings, or exercising any other right afforded to them under the law.[12]

Despite these legal rights, some J-1 teachers may feel unable to participate fully in their unions because of fear of deportation.[13] In addition, while J-1 teachers are fully within their legal rights to participate in work stoppages and other concerted activities, certain visa rules could create uncertainty for these teachers about possible retaliation from sponsor organizations or their employers.[14] The lack of government oversight of recruitment and labor practices in the program is a strong factor in creating an environment rife with intimidation as few formal pathways exist for these educators to report abuses without fear of retaliation.

Teacher Shortages and the J-1 Teacher Program

Teachers and school administrators across the country have decried a shortage of educators for decades. Beginning in early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to an even greater crisis in school staffing shortages, as many teachers either left their jobs for other teaching opportunities, retired early, or chose to leave the profession entirely due to burnout.[15] Especially since visa restrictions were lifted in 2021, school districts seized the opportunity to employ J-1 teachers, filling some of the vacant teaching positions at their schools, at least on a temporary basis. Relying on the recruitment of people from abroad to teach in the United States – even if only for a maximum of five years at a time – is an unsustainable fix to the alleviation of the burden faced by many school administrators and their staff since the start of the pandemic.[16] As a report by the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) about international teacher recruitment notes, “[w]hile the hiring of overseas-trained teachers may be a Band-aid treating the symptom of the teacher shortage, it is in no way a cure for the conditions that caused the shortage in the first place.”[17]

A Case Study of Exploitation in New Mexico

The lack of regulatory structures leaves J-1 teachers vulnerable to abuse. We outline a particularly egregious example below, which made headlines in New Mexico in early 2021.

In January 2021, the New Mexico Attorney General sued a recruitment agency, Total Teaching Solutions International (TTSI), for charging teachers excessive recruitment fees and making misleading statements about the agency’s ability to help teachers obtain J-1 visas. According to the lawsuit, the recruitment agency threatened teachers with lawsuits and deportation if they did not pay their hefty monthly recruitment fees.[18] Furthermore, there were signs of direct collaboration between TTSI and at least one employing school district (for example, the CEO of TTSI was married to the superintendent of the school district in the town of Ruidoso). The lawsuit alleged that TTSI used its association with the superintendent of Ruidoso schools to boost its legitimacy and build connections with other New Mexico School Districts.[19]

The Attorney General’s lawsuit was filed after TTSI sued several J-1 teachers and served them at their schools for allegedly failing to keep up with their exorbitant monthly payments to the agency. These teachers, with the help of their union, AFT, successfully defeated these lawsuits and raised awareness of the exploitative conditions faced by J-1 teachers.[20]

The New Mexico lawsuit is just one example of recruitment agencies overcharging J-1 teachers. Until there is substantial change in the structure and regulations governing the J-1 teacher program, recruitment agencies will continue to charge steep recruitment fees that trap J-1 teachers in a cycle of debt.

Reforms to the J-1 Visa Program Are Needed

Significant regulatory changes are necessary to address widespread problems in the larger J-1 visa program and the exchange visitor teacher program specifically. These reforms must start with the recognition that the J-1 visa program is an employment visa, not solely a cultural exchange program. The State Department therefore needs to formalize a partnership with the DOL to implement the following recommendations. This list is not exhaustive of the necessary changes but addresses the J-1 visa program’s most pressing problems.

1.Oversight is needed

Broad and effective oversight is needed to guarantee that J-1 teachers have robust labor and employment protections, including wage regulations to ensure J-1 teachers are paid no less than their colleagues doing the same work.

2. Regulate recruitment practices

Recruitment practices must be regulated to prohibit recruiters and sponsors from charging recruitment fees to J-1 teachers and hold recruiters and employers jointly liable for abusive recruitment practices, including deceptive promises made during recruitment.

3. Empower J-1 teachers

J-1 teachers must be informed of their legal rights and have effective mechanisms for legal recourse when their rights are violated. J-1 teachers who assert labor and employment or civil rights claims or who are critical to the effective investigation and litigation of such proceedings must have their visas extended, be granted deferred action or other affirmative relief, or be provided with support to apply for U or T visas. Additionally, existing regulations that prohibit employer and sponsor retaliation against J-1 visa program participants who engage in protected activity or assert their rights under local, state, or federal laws must be strengthened and fully enforced. Finally, the regulations that permit program sponsors to suspend J-1 program participants if they “fail to pursue the activities for which he or she was admitted to the United States,” must be clarified to explicitly state that J-1 visa program participants have the right to engage in protected concerted activity under U.S. labor law.

4. Increase transparency of J-1 visa program

The State Department must increase transparency within the J-1 visa program by making information about visa sponsors and beneficiaries publicly available and easily accessible to the public. This includes sponsorship, recruiter, and employer contracts and fees, occupations, wages, employers, job sites, and demographic data.

Lastly, though the J-1 teacher program is administered by the federal government, state and local policymakers also have a role to play since public school systems employ a significant portion of J-1 teachers. The “Code for the Ethical International Recruitment and Employment of Teachers,” developed by education administrators, labor leaders, and academics, provides a template for how state education departments and school districts can engage with the J-1 teacher program responsibly and ensure they do not replicate abusive recruitment practices in their role as employers.[21]

May 2025

[1] 22 USC §2451.

[2] 22 CFR Section 62.24(d).

[3] 22 CFR Section 62.24(k).

[4] 22 CFR Section 62.24(l).

[5] While this factsheet is focused on the experiences of teachers working under the J-1 visa, extensive research has been conducted about the grueling working conditions often faced by those working under the J-1 summer work travel and au pair programs. See, e.g., “Shining a Light on Summer Work.” International Labor Recruitment Working Group. (2019). Retrieved from https://migrationthatworks.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/shining-a-light-on-summer-work.pdf and Costa, Daniel. “Au pair lawsuit reveals collusion and large-scale wage theft from migrant women through State Department’s J-1 visa program.” Economic Policy Institute. (January 15, 2019). Retrieved from

[6] Villagran, Lauren. “Foreign teachers are paying to work in New Mexico public schools. Here's why.” Las Cruces Sun News. (October 16, 2018). Retrieved from https://www.lcsun-news.com/story/news/education/2018/10/16/foreign-teachers-pay-j-1-visas-nm-school-districts/1618327002/.

[7] “Visa Pages: U.S. Temporary Foreign Worker Visas.” Justice in Motion. (January 2020). Retrieved from https://www.justiceinmotion.org/_files/ugd/64f95e_cd79fd93290b461c96a53817f6a02c4b.pdf.

[8] Caravatti, Marie-Louise, et al. “Getting teacher migration and mobility right.” Education International (May 2014): p. 91. Retrieved from https://www.ei-ie.org/en/item/25652:getting-teacher-migration-and-mobility-right.

[9] 22 CFR Section 62.24(f).

[10] Costa, Daniel. “Guestworker diplomacy: J visas receive minimal oversight despite significant implications for the U.S. labor market.” Economic Policy Institute. (July 14, 2011). Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/j_visas_minimal_oversight_despite_significant_implications_for_the_labor_ma/.

[11] U.S. Department of State. “Facts and Figures: BridgeUSA J-1 Visa Basics.” Cached page from January 19, 2024 via Internet Archive. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20250119144837/https://j1visa.state.gov/basics/facts-and-figures/.

[12] 22 CFR Section 62.10(d) states that: “No sponsor or employee of a sponsor may threaten program termination, remove from the program, ban from the program, adversely annotate an exchange visitor's SEVIS record, or otherwise retaliate against an exchange visitor solely because he/she has filed a complaint; instituted or caused to be instituted any proceeding; testified or is about to testify; consulted with an advocacy organization, community organization, legal assistance program or attorney about a grievance or other work-related legal matter; or exercised or asserted on behalf of himself/herself any right or protection.”

[13] Mabe, Rachel. “Trafficking in Teachers.” Oxford American. (August 25, 2020.) Retrieved from https://www.oxfordamerican.org/magazine/item/1963-trafficking-in-teachers.

[14] 22 CFR Section 62.40 states that a J-1 visa program sponsor is supposed to terminate an exchange visitor’s participation in the program if they “fail to pursue the activities for which he or she was admitted to the United States.”

[15] See, e.g., “Here Today, Gone Tomorrow? What America Must Do to Attract and Retain the Educators and School Staff Our Students Need.” American Federation of Teachers. (2022). Retrieved from https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/media/2022/taskforcereport0722.pdf.

[16] See, e.g., Saslow, Eli. “An American Education.” The Washington Post. (October 2, 2022). Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/10/02/teacher-shortage-bullhead-city-arizona/.

[17] “Importing Educators: Causes and Consequences of International Teacher Recruitment.” American Federation of Teachers (2009): p. 25. Retrieved from https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/media/2015/importingeducators0609.pdf.

[18] Carillo, Edmundo. “Suit: New Mexico firm cheats Philippine teachers.” Albuquerque Journal. (January 5, 2021). Retrieved from https://www.abqjournal.com/1533005/lawsuit-nm-company-taking-advantage-of-filipino-teachers.html.

[19] “Lawsuit alleges financial exploitation of immigrant teachers.” AP News. (January 6, 2021). Retrieved from https://apnews.com/general-news-6289008b86bb302fdfa55ce0fb71f4f9.

[20] “AFT fights exploitation of teachers from the Philippines.” American Federation of Teachers. January 27, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.aft.org/news/aft-fights-exploitation-teachers-philippines.

[21] “Code for the Ethical International Recruitment and Employment of Teachers.” Alliance for Ethical International Recruitment Practices. Retrieved from https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/code_intl_recruitment_2017.pdf.

The Case for Reform of the H-1B and L-1 Visa Programs

2025 FACT SHEET

Highlights

The H-1B and L-1 visa programs play an important role in our economy, but current rules allow employers to use them to lower standards for U.S. professionals and people employed on the visas.

Today, employers use the H-1B and L-1 programs to underpay the people employed on the visas, bypass available U.S. workers and recent graduates, displace existing employees, and lower industry standards.

Requiring employers to pay market wages, strengthening worker safeguards, and providing greater oversight and accountability will ensure that the H-1B and L-1 visa programs help attract skilled talent to the United States.

DPE supports reforming the H-1B and L-1 visa programs based on the experiences of union professionals. The more than four million members of DPE’s 24 affiliated unions include U.S. citizens, permanent residents, and people working on nonimmigrant visas. Union professionals also work in industries where employers routinely use the H-1B and L-1 visa programs to lower standards for U.S. workers and people employed on the visas. Reform is needed to ensure that these visa programs live up to their true intent.

The Basics of the H-1B Visa Program

The H-1B visa is the largest nonimmigrant visa program that U.S. employers use to hire people from abroad to work in the United States for a set duration. (Nonimmigrant visas are commonly called guest worker visas, and people employed on nonimmigrant visas are often referred to as guest workers.) Approximately 600,000 people are employed by 50,000 U.S. employers through H-1B visas in a given year.[1] The H-1B visa is controlled by the employer (formally known as the petitioner), not the worker (formally known as the beneficiary).[2]

People employed on an H-1B visa and other nonimmigrant visas are not permitted to stay permanently in the United States. However, the H-1B visa is also a “dual-intent” visa, meaning one can pursue permanent status in the United States through an immigrant visa while a guest worker on an H-1B.[3]

Employers use the H-1B visa program to hire people into “speciality occupations,” which are jobs that typically require at least a bachelor’s degree or equivalent.[4] H-1B workers must either have a bachelor’s degree or higher, have a state license or certification that permits practice in the specialty occupation, or have training or experience in the specialty occupation that is equivalent to completion of a degree.[5]

H-1B visas are typically issued for an initial term of three years and can be renewed for another three years.[6] If the petitioning employer sponsors the worker for an employment-based (EB) immigrant visa, or a “green card,” then the H-1B visa can be extended in one-year increments while the worker waits for an available EB immigrant visa.[7]

Each year the U.S. government makes available 85,000 new, or “initial,” H-1B visas, with 20,000 of those visas set aside for people holding a master’s degree or higher from a U.S. institution of higher education. However, universities and their affiliated nonprofit entities, nonprofit research organizations, and government research organizations are exempt from the annual cap and can hire an unlimited number of H-1B workers. The annual cap also does not apply to any petitions for renewals, changes to the conditions of an H-1B beneficiary’s employment, or requests for new employment.[8]

Employers complete a multistep process to hire people on H-1B visas. An employer first submits a Labor Condition Application (LCA) with the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) that describes the job for which the employer wishes to hire an H-1B worker and identifies the wage level. The DOL does not conduct an extensive review of LCAs, generally only rejecting LCAs if there are obvious errors or inaccuracies. Once an LCA is approved, an employer files an I-129 petition with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), who approves or denies the employer’s petition. (If USCIS approves the I-129 petition and the worker resides outside the United States, the worker must then complete a vetting process through the U.S. Department of State.)

In years when the number of H-1B petitions exceeds the annual cap, USCIS conducts a random lottery to decide which petitions are selected for approval. For many years, employers, particularly the outsourcing companies, have gamed the lottery by filing more petitions than the number of positions they intend to hire for. Employers who game the lottery are generally not interested in hiring a specific worker, they just want access to as many H-1B visas as possible. (USCIS began to address the gaming of the H-1B lottery in 2024 by establishing a “beneficiary centric selection process” that ensures prospective H-1B workers have the same chance of being selected. The total number of registered petitions decreased substantially in the first H-1B lottery after this rule change.[9])