Racial Representation in Professional Occupations: By the Numbers

2021 Joint Fact Sheet

This fact sheet was jointly produced by the Economic Policy Institute and the Department for Professional Employees, AFL-CIO. The authors are Valerie Wilson, Melat Kassa, and Ethan Miller.

The racial wealth gap in the United States is staggering. While the median white family had about $184,000 in family wealth in 2019, the median Black family had only $23,000 in wealth and the median Latinx family had only $38,000.[i] This inequity has roots in many factors, including discriminatory governmental policies, generational wealth transfers, and the racial wage gap, which is fueled in large part by occupational segregation.

Black and Latinx representation in professional occupations

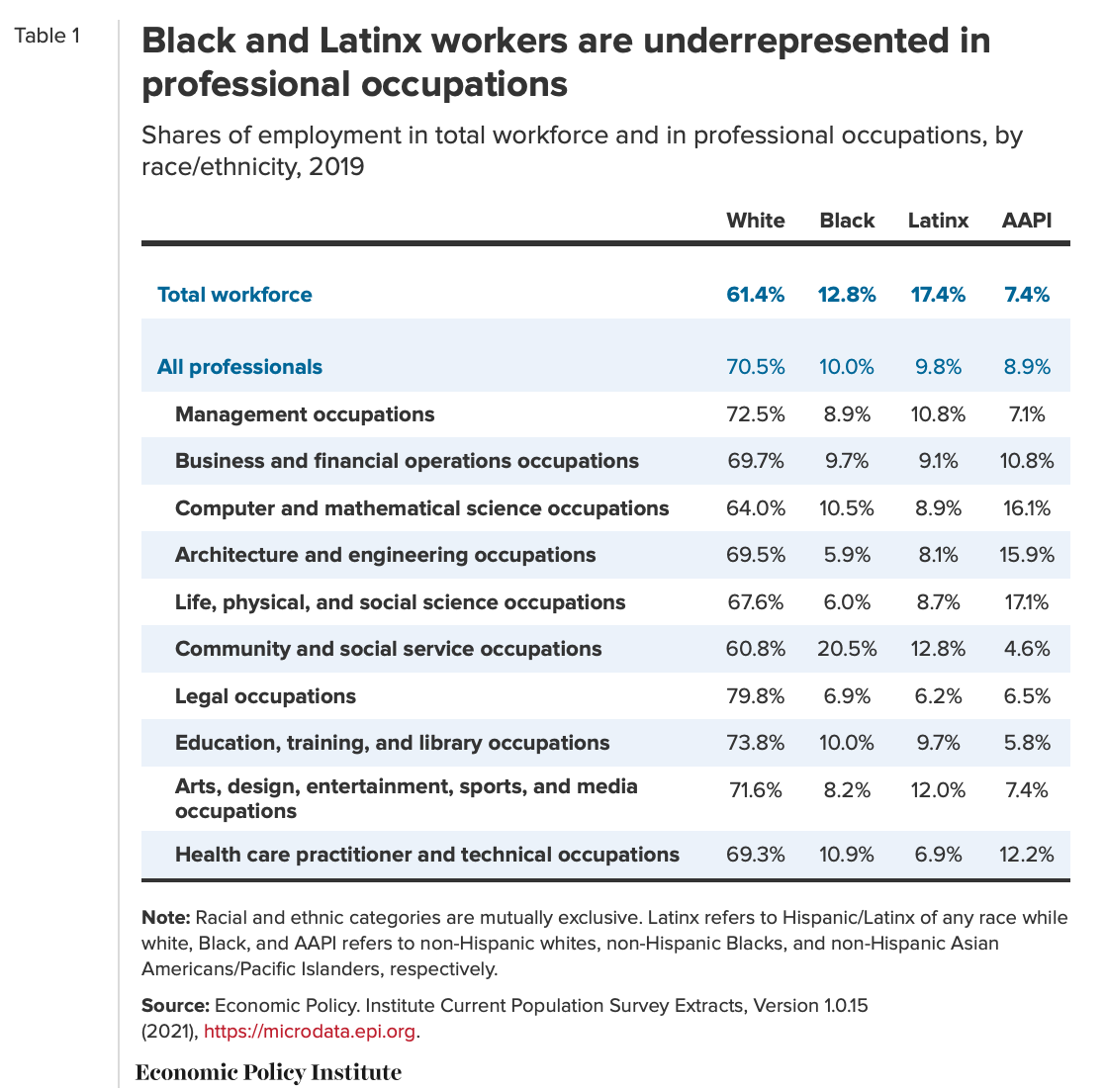

This occupational segregation is observed in the severe underrepresentation of Black and Latinx workers in professional occupations that pay more, on average, than other occupations.[ii] Over the next decade, eight of the 10 major groups of professional occupations are projected to have above-average job growth.[iii] If current disparities in employment patterns remain unchecked, racial disparities in the economy are likely to continue growing.

The data in Table 1 paint a clear picture of the current gap in representation for Black and Latinx workers in professional occupations overall.[iv] But Black and Latinx professionals are also unequally distributed across professional occupation groups. For example, community and social service occupations have much higher rates of representation of Black and Latinx professionals, while others, like legal occupations, lag significantly behind the professional workforce as a whole for both groups. The severe underrepresentation of Black professionals in architecture and engineering, as well as in life, physical, and social sciences, is also notable.

AAPI representation in professional occupations

While representation rates for Black and Latinx professionals generally follow similar patterns, representation for Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) workers does not. As Table 1 shows, AAPI workers are overrepresented in several occupational groups that employ much smaller shares of Black and Latinx workers---especially STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) and health care occupations---while they are underrepresented in those that employ larger shares of Black and Latinx workers, such as community and social service occupations and education, training, and library occupations.

Representation by sector

There are also clear differences in the employment of Black and Latinx professionals across broad sectors of the economy (Table 2). In the federal government and, to a lesser degree, in state and local governments, Black professionals are represented at much higher rates than in the private sector. Historically, the public sector has been a source of equitable job opportunities for Black professionals due to a combination of factors, including strong anti-discrimination and affirmative action regulations.[v] Latinx professionals are more likely to be employed in local government or for-profit private-sector companies.

Fast growth is projected in professional occupations—which may exacerbate inequality

Today’s inequities are of particular concern because several professional occupational categories are projected to grow at faster rates than the overall workforce. While the overall workforce is projected to grow by 3.7% from 2019–2029, the professional workforce is projected to grow at an average rate of 6.4%.[vi] In particular, computer and mathematical occupations, community and social service occupations, and health care practitioner and technical occupations are projected to grow at above-average rates.

Given underrepresentation of Black and Latinx workers in these occupations, and given that these occupations pay higher wages than other occupations, faster growth in these fields will exacerbate inequality if the problem of underrepresentation is not addressed.

While there has been some improvement in the representation rates of Black and Latinx professionals since the year 2000, the rate of change has been so slow that, if we continued at that rate, it would take 38 years to overcome the representational gap for Black professionals and 33 years for Latinx professionals.[vii] However, this does not take into account the fact that Black and Latinx shares of the overall workforce are projected to continue increasing over the next decade or more, lengthening the amount of time until this gap is overcome.[viii]

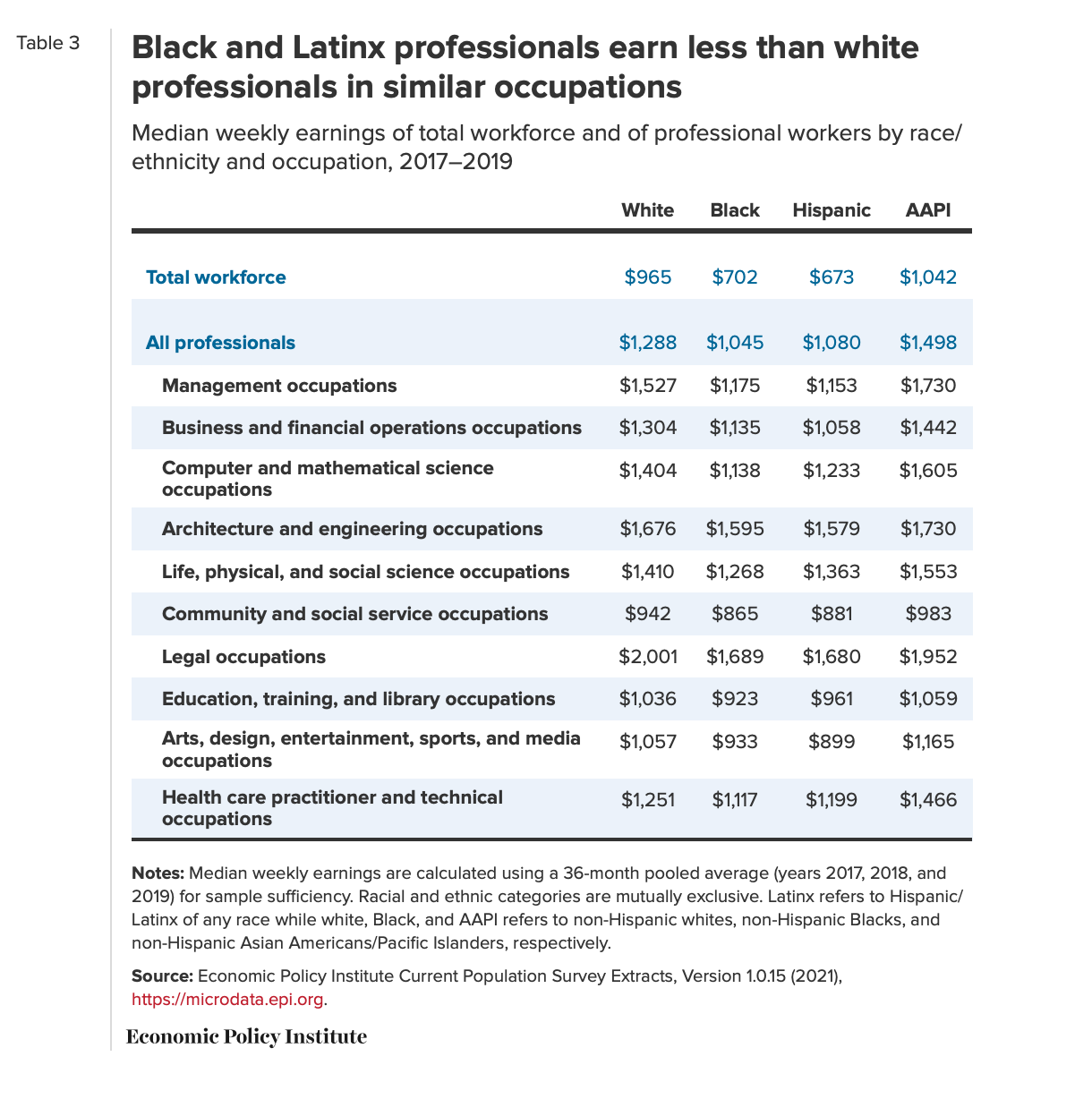

Pay disparities persist within professional occupations

On average, professionals are paid 44% more than the median wage earned by workers in all occupations. The underrepresentation of Black and Latinx workers in professional occupations is therefore an important factor in the racial wage gap. But there is a compounding factor: Black and Latinx workers who are in professional occupations still earn less than their white counterparts in similar occupations (Table 3).

Occupational segregation and discrimination are significant factors in explaining racial wage gaps, and these pay gaps are signs of the larger structural inequities that Black and Latinx professionals face in the workplace that impact related outcomes such as promotions, recruitment, and retention.[ix]

Policy recommendations

In order to close the professional representational gap at a faster rate and address other inequities in professional occupations, many changes are needed at the federal, state, local, and workplace levels. The following five recommendations are not an exhaustive list of the necessary changes but should be seen as a starting place for policymakers looking to tackle these challenges.

Increase the ability for professionals of all races and ethnicities to organize and join unions

Representation rates for Black and Latinx professionals are higher in jobs that are covered by union contracts. According to EPI analysis, Black professionals make up 10.9% of all professionals in unions compared with 9.6% of professionals not in unions, and Latinx professionals make up 10.4% of professionals in unions compared with 9.5% of professionals not in unions.[x] Union positions, on average, pay higher wages than nonunion jobs, and union contracts often have provisions that take subjectivity and bias out of the promotion and advancement process, increasing opportunities for Black and Latinx professionals to move up and remain in their chosen occupations.

While professionals of all races benefit from union coverage, the improvements won through a union are often greater for Black and Latinx workers: Among all occupations in 2019, Black workers who were covered by a union contract were paid 26.7% more than their nonunionized counterparts, and Latinx workers covered by a union contract were paid 35% more than their nonunionized peers. For comparison, the pay premium for all workers covered by a union contract in 2019 was 21.3%.[xi]

Union membership and collective bargaining empower professionals to challenge the workplace discrimination that contributes significantly to the underrepresentation of Black and Latinx professionals, especially in the tech sector. Research from the Kapor Center for Social Impact highlights how unfair treatment is the most frequent reason that Black and Latinx professionals leave tech jobs.[xii]

However, only 11.3% of professionals were union members in 2020.[xiii] U.S. labor law makes organizing new unions very difficult, and there are few, if any, negative consequences for employers who break the law to stop a union drive.

Significant reforms are needed to remove barriers to accessing the fundamental right to organize and bargain for improved working conditions and expanded opportunities for Black and Latinx professionals to be employed and advance in professional occupations.[xiv] The Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, introduced in Congress in 2021, would do just that by modernizing U.S. labor law and strengthening penalties for employers who break the law to discourage employees from organizing new unions.[xv]

Strengthen anti-discrimination laws in the private sector

While the representation of Black and Latinx professionals has increased over the last 20 years, their representation in the private sector lags significantly behind their representation in the public sector, as noted above.

Strengthening labor law and anti-discrimination policies are important steps toward creating a more equitable and diverse professional labor force in all sectors. The Restoring Justice for Workers Act, first introduced in Congress in 2019, would prohibit private-sector employers from requiring new hires to sign mandatory arbitration agreements.[xvi] Such agreements prevent working people from seeking justice through the judicial system for violations of their workplace rights, including Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin.[xvii]

Workplace culture and rules are often shaped by the norms and practices of the racial majority, resulting in discrimination against those who are outside of those norms. One proposal to counter this type of workplace culture is the Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair (CROWN) Act, which would protect against discrimination based on race-based hairstyles such as braids, locs, twists, and knots.[xviii]

Dismantle structures that perpetuate pay gaps

Large racial and gender wage gaps persist even when comparing workers with similar education, experience, and geographic location, revealing discrimination as a major factor.[xix] In 2016, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) revised the Employment Information Report (EEO-1) to require large employers to report what they pay their employees by job category, sex, race, and ethnicity. This policy was introduced to strengthen enforcement of anti-discrimination laws and to draw employers’ attention to discriminatory pay disparities that may otherwise go undetected. Consistent and systematic collection of pay data also provides another layer of detail to existing reports of employment used to detect discriminatory hiring and promotion practices. However, in 2017, the Trump administration stayed the pay data collection rule, ending the reporting requirement. This rule needs to be reinstated.

An additional, complementary policy would prohibit employers from asking job candidates about previous pay history. As early as 2016, several states and localities began regulating the use of salary history during the hiring process.[xx] Implementing such a policy at the federal level would help to untether Black and Latinx professionals from lower levels of pay throughout their careers.

Remove barriers to job access for Black and Latinx professionals in STEM

The hiring of Black and Latinx professionals in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields lags behind hiring in other professional occupations. One possible barrier that contributes to this reality is the H-1B visa program, which allows employers to hire temporary migrant workers at below-market wages. Because their immigration status is controlled by their employers, it is difficult in practice for H-1B beneficiaries to seek out new jobs and it is difficult for them to exercise their workplace rights and advocate for better wages or improved working conditions.[xxi] According to the U.S. Department of Labor, H-1B workers account for approximately 10% of employment in information technology and, in certain key occupations---like software developers working on applications---they account for a remarkable 22%;[xxii] the share is likely even higher in certain geographies.

Since most employers are not required to advertise jobs to U.S. professionals before hiring through the H-1B visa program,[xxiii] they have access to a ready supply of underpaid and immobile workers and have little incentive to invest in recruitment, training, or retention initiatives for Black and Latinx professionals.

The H-1B visa program must be reformed to ensure that migrant workers have equal rights and are paid fairly. By uplifting labor standards in the H-1B program, we can ensure that it no longer serves as a barrier to Black and Latinx professionals accessing and retaining jobs in STEM occupations.[xxiv]

Increase federal arts funding and leverage tax incentives to create talent pipelines and encourage diverse hiring in the arts, entertainment, and media industries

The National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting help bolster local economies and put creative professionals to work on nonprofit productions and performances. Federal policymakers can help ensure that more of these career opportunities are available to underrepresented professionals by increasing federal arts funding overall and working with the unions that represent creative professionals to develop diversity-hiring requirements and reporting objectives for grant recipients. Additionally, Congress should follow the lead of states like Illinois, New Jersey, and New York to expand existing tax credits for American-based film, television, and live entertainment productions and identify effective diversity requirements for these tax incentives that will spur more inclusive hiring in film, television, and live entertainment.[xxv]

Notes

[i] Ana Hernández Kent and Lowell R. Ricketts, “Wealth Gaps Between White, Black and Hispanic Families in 2019,” On the Economy Blog (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis), January 5, 2021.

[ii] As defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, professional occupations include management occupations; business and financial operations occupations; computer and mathematical occupations; architecture and engineering occupations; life, physical, and social science occupations; community and social service occupations; legal occupations; educational instruction and library occupations; arts, design, entertainment, sports, and media occupations; and health care practitioner and technical occupations.

[iii] According to BLS projections, employment in all occupations is expected to grow 3.7% between 2019 and 2029. The major occupational groups expected to grow faster include community and social service occupations (12.5%); computer and mathematical occupations (12.1%); health care practitioner and technical occupations (9.1%); business and financial operations occupations (5.3%); legal occupations (5.1%); management occupations (4.7%); life, physical, and social science occupations (4.7%); and educational instruction and library occupations (4.5%). See “Table 1.1. Employment by Major Occupational Group, 2019 and Projected 2029,” Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment Projections, last updated April 9, 2021.

[iv] Because of the large and anomalous labor market fluctuations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and economic recession in 2020, we base the analysis in this fact sheet on data from 2019 and earlier.

[v] David Cooper and Julia Wolfe, “Cuts to the State and Local Public Sector Will Disproportionately Harm Women and Black Workers,” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), July 9, 2020.

[vi] “Table 1.1. Employment by Major Occupational Group, 2019 and Projected 2029,” Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment Projections, last updated April 9, 2021.

[vii] Economic Policy Institute Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.15 (2021). Annual rate of change is based on authors’ analysis of the change in representation of Black and Latinx workers in professional occupations from 2000 to 2019 and their overall representation in the workforce in 2019. In the year 2000, white professionals made up 80.3% of the entire professional workforce, with Black and Latinx professionals making up just 8.5% and 5.2%, respectively.

[viii] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Hispanic Share of the Labor Force Projected to Be 20.9 Percent by 2028,” TED: The Economics Daily, October 2, 2019.

[ix] Kim Weeden, “Occupational Segregation,” Pathways: A Magazine on Poverty, Inequality, and Social Policy (Special Issue 2019): 33–36.

[x] Economic Policy Institute Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.15 (2021).

[xi] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 2. Median Weekly Earnings of Full-Time Wage and Salary Workers by Union Affiliation and Selected Characteristics” (economic news release), January 22, 2021.

[xii] Allison Scott, Freada Kapor Klein, and Uriridiakoghene Onovakpuri, Tech Leavers Study, Kapor Center for Social Impact, April 2017.

[xiii] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 3. Union Affiliation of Employed Wage and Salary Workers by Occupation and Industry” (economic news release), January 22, 2021.

[xiv] Department for Professional Employees, AFL-CIO, Toolkit: Advancing Racial Justice in the Professional Workplace, July 2020.

[xv] Celine McNicholas, Margaret Poydock, and Lynn Rhinehart, Why Workers Need the Protecting the Right to Organize Act (fact sheet), Economic Policy Institute, February 2021.

[xvi] Celine McNicholas, “The Restoring Justice for Workers Act Is a Crucial First Step Toward Shifting the Balance of Power Between Workers and Employers” (statement), Economic Policy Institute, May 15, 2019.

[xvii] Alexander J.S. Colvin, The Growing Use of Mandatory Arbitration, Economic Policy Institute, April 2018.

[xviii] Candice Norwood, “A Yearslong Push to Ban Hair Discrimination Is Gaining Momentum,” PBS NewsHour, March 30, 2021.

[xix] Valerie Wilson and William M. Rodgers III, Black-White Wage Gaps Expand with Rising Wage Inequality, Economic Policy Institute, September 2016.

[xx] AAUW, “State and Local Salary History Bans” (interactive map), accessed June 3, 2021.

[xxi] Daniel Costa and Ron Hira, H-1B Visas and Prevailing Wage Levels: A Majority of H-1B Employers—Including Major U.S. Tech Firms—Use the Program to Pay Migrant Workers Well Below Market Wages, Economic Policy Institute, May 2020. See also U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Modification of Registration Requirement for Petitioners Seeking to File Cap-Subject H-1B Petitions, 86 Fed. Reg. 1676, at Table 7, page 1720, showing that 85% of new H-1B petitions went to employers paying at wage level 1 or 2, and 90% of petitions for the advanced degree exemption were awarded to employers paying at wage levels 1 and 2. Both wage levels 1 and 2 are below the local median wage for the specific occupation.

[xxii] Employment and Training Administration, U.S. Department of Labor, Strengthening Wage Protections for the Temporary and Permanent Employment of Certain Aliens in the United States, Final Rule, 86 Fed. Reg. 3608, January 14, 2021.

[xxiii] Daniel Costa, H-1B Visa Needs Reform to Make It Fairer to Migrant and American Workers (fact sheet), Economic Policy Institute, April 5, 2017.

[xxiv] Department for Professional Employees, AFL-CIO, The H-1B Temporary Visa Program’s Impact on Diversity in STEM (fact sheet), March 2020.

[xxv] Department for Professional Employees, AFL-CIO, A Policy Agenda for Advancing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) in the Arts, Entertainment, and Media Industries, February 2021.