The Case for Reform of the H-1B and L-1 Visa Programs

2026 FACT SHEET

Highlights

The H-1B and L-1 visa programs play an important role in our economy, but current rules allow employers to use the visas to lower standards for U.S. professionals and people employed on the visas.

Today, employers use the H-1B and L-1 programs to underpay the people employed on the visas, bypass available U.S. workers and recent graduates, displace existing employees, and lower industry standards.

Requiring employers to pay market wages, strengthening worker safeguards, and providing greater oversight and accountability will ensure that the H-1B and L-1 visa programs help attract skilled talent to the United States.

DPE supports reforming the H-1B and L-1 visa programs based on the experiences of union professionals. The more than four million members of DPE’s 24 affiliated unions include U.S. citizens, permanent residents, and people working on nonimmigrant visas. Union professionals also work in industries where employers routinely use the H-1B and L-1 visa programs to lower standards for U.S. workers and people employed on the visas. Reform is needed to ensure that these visa programs live up to their true intent.

The Basics of the H-1B Visa Program

The H-1B visa is the largest nonimmigrant visa program that U.S. employers use to hire people from abroad to work in the United States for a set duration. (Nonimmigrant visas are commonly called guest worker visas, and people employed on nonimmigrant visas are often referred to as guest workers.) Approximately 600,000 people are employed by 50,000 U.S. employers through H-1B visas in a given year.[1] The H-1B visa is controlled by the employer (formally known as the petitioner), not the worker (formally known as the beneficiary).[2]

People employed on an H-1B visa and other nonimmigrant visas are not permitted to stay permanently in the United States. However, the H-1B visa is also a “dual-intent” visa, meaning one can pursue permanent status in the United States through an immigrant visa while a guest worker on an H-1B.[3]

Employers use the H-1B visa program to hire people into “speciality occupations,” which are jobs that typically require at least a bachelor’s degree or equivalent.[4] H-1B workers must either have a bachelor’s degree or higher, have a state license or certification that permits practice in the specialty occupation, or have training or experience in the specialty occupation that is equivalent to completion of a degree.[5]

H-1B visas are typically issued for an initial term of three years and can be renewed for another three years.[6] If the petitioning employer sponsors the worker for an employment-based (EB) immigrant visa, or a “green card,” then the H-1B visa can be extended in one-year increments while the worker waits for an available EB immigrant visa.[7]

Each year the U.S. government makes available 85,000 new, or “initial,” H-1B visas, with 20,000 of those visas set aside for people holding a master’s degree or higher from a U.S. institution of higher education. However, universities and their affiliated nonprofit entities, nonprofit research organizations, and government research organizations are exempt from the annual cap and can hire an unlimited number of H-1B workers. The annual cap also does not apply to any petitions for renewals, changes to the conditions of an H-1B beneficiary’s employment, or requests for new employment.[8]

Employers complete a multistep process to hire people on H-1B visas. An employer first submits a Labor Condition Application (LCA) with the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) that describes the job for which the employer wishes to hire an H-1B worker and identifies the wage level. The DOL does not conduct an extensive review of LCAs, generally only rejecting LCAs if there are obvious errors or inaccuracies. Once an LCA is approved, an employer files an I-129 petition with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), who approves or denies the employer’s petition. (If USCIS approves the I-129 petition and the worker resides outside the United States, the worker must then complete a vetting process through the U.S. Department of State.)

In years when the number of H-1B petitions exceeds the annual cap, USCIS sets a process for allocating the visas. Traditionally, USCIS conducted a random lottery to decide which petitions are selected for approval. For many years, employers, particularly the outsourcing companies, gamed the lottery by filing more petitions than the number of positions they intend to hire for. Employers who gamed the lottery were generally not interested in hiring a specific worker, they just wanted access to as many H-1B visas as possible.

USCIS began to address the gaming of the H-1B lottery in 2024 by establishing a “beneficiary centric selection process” that ensures prospective H-1B workers have the same chance of being selected. The total number of registered petitions decreased substantially in the first H-1B lottery after this rule change.[9] Starting with the Fiscal Year 2027 visa allocation process, USCIS moved to a weighted selection process, which is intended to increase the probability that petitions promising to pay higher wages are selected ahead of petitions for employers that will offer lower wages to H-1B workers.

Even with recent changes to the visa allocation process, the H-1B program lacks the safeguards that most Americans would expect of a work visa program. In practice, H-1B employers are not required to first recruit available, qualified U.S. workers, nor are they prohibited from replacing existing employees with H-1B workers.[10] In general, H-1B employers must only attest: (1) “that they will pay H-1B workers the amount they pay other employees with similar experience and qualifications or the prevailing wage; (2) that the employment of H-1B workers will not adversely affect the working conditions of U.S. workers similarly employed; (3) that no strike or lockout exists in the occupational classification at the place of employment; and (4) that the employer has notified employees at the place of employment of the intent to employ H-1B workers.”[11] However, even enforcement of these attestations is lacking.[12]

The B-1 in Lieu of H-1B Workaround

The B-1 visa is not a work visa. It is intended for visitors to the United States, including people who travel here for business purposes on a very short-term basis, such as attending a conference. Yet employers can use what is called “B-1 in lieu of H-1B” status to bring international workers otherwise eligible for the H-1B program to work in the United States. The U.S. government does not release data on the annual number of B-1 in lieu of H-1B status approvals, durations of stay, type of work involved, or connected employers.

The B-1 in lieu of H-1B status enables employers to cut labor costs and facilitate the offshoring of work without having to comply with the H-1B program’s rules or compete for cap-subject visas.[13] For example, in 2011, the Boeing Company attempted to bring 18 Russian contractors from its Moscow engineering and design center to the United States using B-1 in lieu of H-1B status. The Russian contractors were denied entry at the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport by immigration officials after admitting that they would be working, and not receiving training as they were coached to say. The Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace (SPEEA), the union representing engineers at Boeing, reported that at the time, Boeing had between 75 and 200 Russian engineers working at Boeing in Seattle on B-1 in lieu of H-1B status. If the Russian engineers had been on H-1B visas, then Boeing would have to pay them wages set forth in the collective bargaining agreement. Instead, the Russian engineers were paid wages that were one-third to one-fifth of what the U.S. Boeing engineers made.[14]

Quantifying the H-1B Visa Workforce

Approximately 600,000 people are employed on H-1B visas at any time.[15] They work for about 50,000 employers who have filed new, continuing, or amended H-1B petitions. The majority of approved H-1B petitions are for continuing rather than initial employment, making up on average 69 percent of approved petitions between 2019 and 2023.[16] In fiscal year 2023, most H-1B approved petitions were for beneficiaries from India or China, together making up 84 percent of all approved H-B petitions that year.[17]

The majority of H-1B workers identify as male and are highly concentrated in STEM fields, especially in computer-related occupations. Since fiscal year 2014, at least 60 percent of the H-1B visas approved each year have gone to workers in computer-related occupations.[18] In fiscal year 2023, 70.5 percent of approved H-1B petitions went to beneficiaries identifying as male, while 29.3 percent went to beneficiaries identifying as female.[19] This population usually skews younger; in 2023, a majority of beneficiaries were between 25 and 39 years old, with a third of beneficiaries between the ages of 30 and 34.[20]

The vast majority of H-1B workers hold a bachelor’s degree, and about a third of H-1B workers have a master’s, doctorate, or professional degree.[21]

Ineffectual Rules Promote Employer Misuse

The H-1B visa program must be reformed so that employers can no longer use the program to lower industry standards, engage in outsourcing and offshoring, and pay H-1B workers below market wages in often exploitative work arrangements.

Employers Can and Do Underpay H-1B Workers

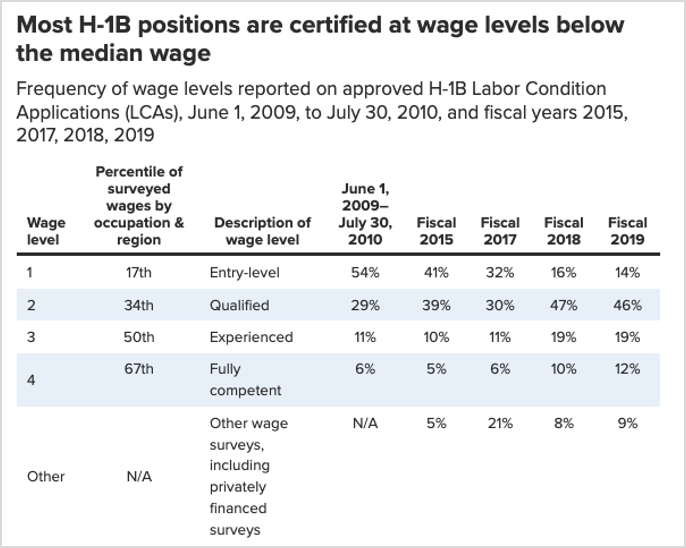

The H-1B visa program’s prevailing wage standard is set by three factors: occupation, location, and skill level. For an H-1B worker, in a given job and in a given location, the employer can pay one of four levels based in part on the job requirements, which is determined by the employer. Level 1 is considered an “entry level” position whose pay is set at the 17th percentile of wages for the occupation and area; Level 2 pay is set at the 34th percentile of wages for an occupation and area; Level 3 pays the local median wage; and Level 4 wages are at the 67th wage percentile for the occupation and area. In fiscal year 2019, 60 percent of H-1B positions were paid at the lowest two levels, meaning they were paid below the median wage for the occupation and location.

Source: Costa, Daniel and Ron Hira. “H-1B visas and prevailing wage levels.” (May 2020). Economic Policy Institute. [see footnote 23].

Outsourcing and offshoring companies have built their business models around the ability to legally pay H-1B workers less than the median wage for an occupation and geographic area. Outsourcers are regularly among the top H-1B employers, receiving an outsize share of all cap-subject H-1B visas each year. Internal corporate strategy documents confirm that these companies see the ability to underpay H-1B workers as a competitive advantage that supports their business model. In internal documents made public as part of a federal whistleblower lawsuit, HCL Technologies, a tech outsourcing company based in India, emphasized its plan to lower labor costs by intentionally paying H-1B workers less than U.S. workers. The amount of underpayment was “estimated … to likely exceed $95 million annually.”[22] However, all types of companies, including big-name tech firms, take advantage of the H-1B visa program’s low wage levels. For example, Amazon and Microsoft each paid three-fourths or more of their H-1B positions at the two lowest wage levels, and Google paid over one-half at the second lowest wage level.[23] Furthermore, the DOL does not conduct oversight or otherwise regularly ensure that companies are complying with wage levels appropriate for the job title.[24]

Employers can replace U.S. professionals with H-1B workers, enabling the outsourcing and offshoring of professional careers

Employers, particularly outsourcing and offshoring companies, also take advantage of the H-1B visa program’s lack of recruitment requirements and displacement safeguards. In 2022, nearly 40 percent of all H-1B visas were issued to just 30 employers, 17 of which were companies where the primary business model is based on outsourcing. These firms alone were issued 20,000 H-1B visas, nearly one-quarter of the total 85,000 annual limit for cap-subject visas.[25]

There are numerous examples of employers using the H-1B program to replace existing workers. In 2015, the Walt Disney Company replaced about 250 IT professionals at Disney World with H-1B workers employed by HCL America and Cognizant.[26] Similar incidents have occurred at Southern California Edison,[27] AT&T,[28] MassMutual Financial Group,[29] and many other well-known companies.

Public sector employers also use the H-1B program to lower standards and privatize jobs. In 2017, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) eliminated nearly 100 IT jobs and replaced them with H-1B workers who worked for the Indian outsourcing company HCL Technologies.[30] Congressional representatives from California spoke out against this practice, leading UCSF to alter their hiring plan, which many viewed as a temporary move that did not fully address the issue.[31] In 2020, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a federally-owned electric utility corporation, planned to outsource hundreds of IT jobs through the H-1B visa program with the assistance of foreign-owned tech outsourcing firms. Tech professionals at the TVA, who were union members of the International Federation of Professional and Technical Engineers (IFPTE), sounded the alarm,[32] which ultimately led to interventions by the Trump Administration to prohibit the TVA from laying off its U.S.-based IT workers.[33]

In many cases, the displaced U.S. employees are required to train their H-1B replacements as a final job assignment in order to qualify for severance.[34] Requiring U.S. professionals to train their H-1B replacements facilitates “knowledge transfer,” a degrading process whereby displaced employees train their replacements on every single part of their job, often down to the exact keystrokes.[35] The replacement H-1B worker will then use the newly learned skills to either do the exact same job in the U.S. at lower wages or take the skills back to their home country as part of the employer’s offshoring of the work. The prevalence of knowledge transfer among H-1B employers, particularly outsourcing and offshoring companies, challenges the notion that employers cannot find available, qualified U.S. professionals.

Minimal Protections for H-1B Beneficiaries and Little DOL Oversight

Along with paying sub-standard wages, companies can use their control of the H-1B visa to take advantage of H-1B workers in other ways. Employers can require H-1B workers to work longer hours, skip holidays, and miss scheduled pay increases.[36] If an H-1B worker says no, they risk being terminated and losing their legal status in the United States. H-1B employers can therefore use their virtual total control over whether an H-1B worker continues to live in the United States to intimidate workers into not speaking out or filing complaints with labor agencies.

The DOL is faced with numerous obstacles in its ability to protect H-1B workers, including lack of authority to initiate investigations, inability to access the Labor Condition Application database, inadequate fines for employer noncompliance with a DOL investigation, and lack of subpoena authority to obtain employer records.[37]

The Basics of the L-1 Visa Program

The L-1 visa is intended to be used by multinational corporations to transfer employees employed abroad to a branch, parent, affiliate, or subsidiary of that same employer in the United States. Experts estimate that there are between 310,000 and 337,000 L-1 workers in the United States at any time.[38] The L-1 visa is largely a black box. There is no publicly available data showing how much L-1 workers are paid or the duration of their stays.

For employers to be eligible to use the L-1 visa program, the petitioning company must have employed the L-1 worker within the three preceding years and have continuously employed the worker abroad for one year.[39] There are two classes, the L-1A visa is for managers and executives and the L-1B visa is for employees with “specialized knowledge.”[40] Specialized knowledge refers to “special knowledge possessed by an individual of the petitioning organization’s product, service, research, equipment, techniques, management, or other interests and its application in international markets, or an advanced level of knowledge or expertise in the organization’s processes and procedures.”[41]

For L-1 workers entering the United States to establish a new office, the initial term of the L-1 visa is one year, while L-1 visas covering all other employees have initial terms of three years. The L-1 visa is renewable for up to seven years total for supervisors[42] and five years for other qualified employees.[43]

Much like the H-1B visa, it is the employer who has control over the terms of the L-1 visa, not the worker.[44] There is no wage requirement, meaning an employer can pay an L-1 worker their home country wage rate or less. (L-1 worker wages technically must be the higher of the state or federal minimum wage, but compliance enforcement is virtually nonexistent.) Additionally, the L-1 visa program is uncapped.

Employers Take Advantage of L-1 Visa Program’s Minimal Worker Protections and Overly Broad Definition of “Specialized Knowledge”

From an employer’s perspective, L-1 visas are desirable because there are no minimum wage requirements. Employers can legally pay well below the market wage, offshore work, and displace U.S. workers. Employers only face consequences when they are caught failing to meet the lowest of labor standards. For example, in late 2013, tech company Electronics for Imaging was fined by DOL and ordered to pay back wages to nonimmigrant workers who were paid just $1.21 per hour to work 120 hours per week installing computer systems in California. The employees were likely on L-1 visas. Since there is no prevailing wage requirement, the company was only required to pay its foreign employees the state minimum wage.[45]

Employers often take advantage of an overly broad definition of “specialized knowledge” for the L-1B visa to bring employees to the United States, which in many cases facilitates offshoring. Even the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General pointed out that “specialized knowledge” is defined so broadly that “almost every petition could reasonably be approved.”[46] Much in the same way that H-1B employers have offshored jobs through knowledge transfer, L-1 employers can bring their foreign national employees to train in the United States and then export that knowledge (along with the employee) back to their home country under the cover of “specialized knowledge,” and they can do so for even less cost than using the H-1B program.[47]

Policy Recommendations

The H-1B and L-1 visa programs must be reformed so that they work for U.S. professionals and people working on the visas, not just employers. The following policy recommendations are informed by the lived experiences of union professionals.

Require recruitment of available, qualified U.S. workers.

Employers should be required to demonstrate good faith recruitment of available, qualified U.S. workers and offer the job to a qualified U.S. applicant before hiring through the H-1B or L-1 visa programs.

2. Prevent the displacement of existing employees.

Prohibit contractors and direct employers from laying off, terminating, or demoting an employee in order to replace that worker with a nonimmigrant.

3. Impose equitable wage standards.

Increase the H-1B minimum wage to no less than the median wage for the relevant occupation and area and establish minimum wage standards for the L-1 program.

4. Adopt a wage-based visa allocation process.

Adopt a wage-based visa allocation process that prioritizes international graduates who earned advanced degrees from U.S. colleges and universities while physically present in the United States and offered jobs at the highest wage level.

5. Empower workers to report workplace violations.

Ensure nonimmigrants and U.S. workers are able to report workplace violations without fear of retaliation and require regular DOL audits to ensure employer compliance with visa program rules.

6. Allow H-1B and L-1 nonimmigrants to self-petition for permanent status.

Allow H-1B and L-1 nonimmigrants to self-petition for permanent status and provide them the freedom to change jobs while waiting for available immigrant visas.

[1] Costa, Daniel and Ron Hira. “Tech and outsourcing companies continue to exploit the H-1B visa program at a time of mass layoffs.” (April 11, 2023). Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/blog/tech-and-outsourcing-companies-continue-to-exploit-the-h-1b-visa-program-at-a-time-of-mass-layoffs-the-top-30-h-1b-employers-hired-34000-new-h-1b-workers-in-2022-and-laid-off-at-least-85000-workers/.

[2] 8 CFR §214.2(h)

[3] U.S. Department of State. Foreign Affairs Manual. 9 FAM 402.10-10(A). Retrieved from https://fam.state.gov/.

[4] The H-1B visa is also used for fashion models who work in the United States on a temporary basis.

[5] 8 CFR §214.2(h).

[6] Employers involved in DOD research and development projects can petition for H-1B visas that are valid for five years and able to be renewed for another five year period.

[7] 8 CFR §214.2(h).

[8] Ibid.

[9] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “H-1B Electronic Registration Process.” (March 31, 2025). Retrieved from https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/temporary-workers/h-1b-specialty-occupations/h-1b-electronic-registration-process.

[10] “H-1B Dependent Employers,” employers with 15% or more employees working H-1B visas, must follow recruitment and nondisplacement requirements unless they are paying H-1B workers at least $60,000. In practice, virtually all H-1B Dependent Employers pay H-1B workers at least $60,000 to avoid the additional requirements.

[11] Government Accountability Office. “H-1B Program: Reforms Needed to Minimize the Risks and Costs of Current Program.” (January 2011). Retrieved from https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-11-26.pdf

[12] See, e.g., Hira, Ron and Daniel Costa. “New evidence of widespread wage theft in the H-1B visa program.” (December 9, 2021). Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/new-evidence-widespread-wage-theft-in-the-h-1b-program/.

[13] See, e.g., Hira, Ron. “Congressional Testimony: Immigration Reforms Needed to Protect Skilled American Workers.” (March 17, 2015). Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/congressional-immigration-reforms-needed-to-protect-skilled-american-workers/; and Novinson, Michael. “Boosting U.S. IT Skills Or Replacing U.S. Workers? H-1B Visas In The Crosshairs.” (September 8, 2015). CRN. Retrieved from https://www.crn.com/news/channel-programs/300077929/boosting-u-s-it-skills-or-replacing-u-s-workers-h-1b-visas-in-the-crosshairs.

[14] Gates, Dominic. “Russian engineers, once turned back, now flowing to Boeing again.” (April 15, 2012). The Seattle Times. Retrieved from https://www.seattletimes.com/business/russian-engineers-once-turned-back-now-flowing-to-boeing-again/.

[15] Costa, Daniel and Ron Hira. “Tech and outsourcing companies continue to exploit the H-1B visa program at a time of mass layoffs.” [above, n. 1].

[16] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers: Fiscal Year 2023 Annual Report to Congress.” (March 6, 2024). Appendix D, Table 1b. Retrieved from https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/reports/OLA_Signed_H-1B_Characteristics_Congressional_Report_FY2023.pdf.

[17] Ibid., Appendix D, Table 4a.

[18] Im, Carolyne, Alexandra Cahn, and Sahana Mukherjee. “What we know about the U.S. H-1B visa program.” (March 4, 2025). Pew Research. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/03/04/what-we-know-about-the-us-h-1b-visa-program/.

[19] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers.” Appendix D, Table 5. [above, n. 16].

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid., Table 6.

[22] See, e.g., Hira, Ron and Daniel Costa. “New evidence of widespread wage theft in the H-1B visa program.” [above, n. 12].

[23] Costa, Daniel and Ron Hira. “H-1B visas and prevailing wage levels.” (May 2020). Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/h-1b-visas-and-prevailing-wage-levels/.

[24] Costa, Daniel and Ron Hira. “EPI comments on DOL Request for Information on determining prevailing wage levels for H-1B visas and permanent labor certifications for green cards.” (June 1, 2021). Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/epi-comment-on-prevailing-wage-levels-determination-for-h-1b-visas-and-permanent-labor-certifications-for-green-cards/.

[25] Costa, Daniel and Ron Hira. “Tech and outsourcing companies continue to exploit the H-1B visa program at a time of mass layoffs.” [above, n. 1]. See also Fan, Eric, Zachary Mider, Denise Lu, and Marie Patino. “How Thousands of Middlemen are Gaming the H-1B Program.” (July 31, 2024). Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2024-staffing-firms-game-h1b-visa-lottery-system/.

[26] Preston, Julia. “Lawsuits Claim Disney Colluded to Replace U.S. Workers With Immigrants.” The New York Times. (January 25, 2016). Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/26/us/lawsuit-claims-disney-colluded-to-replace-us-workers-with-immigrants.html.; see also Preston, Julia. “Pink Slips at Disney. But First, Training Foreign Replacements.” (June 4, 2015). The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/04/us/last-task-after-layoff-at-disney-train-foreign-replacements.html.

[27] Thibodeau, Patrick. “Southern California Edison IT workers ‘beyond furious’ over H-1B replacements.” (February 2015). ComputerWorld. Retrieved from https://www.computerworld.com/article/2879083/southern-california-edison-it-workers-beyond-furious-over-h-1b-replacements.html.

[28] Kight, Stef W. “U.S. companies are forcing workers to train their own foreign replacements.” (December 2019). Axios. Retrieved from https://www.axios.com/trump-att-outsourcing-h1b-visa-foreign-workers-1f26cd20-664a-4b5f-a2e3-361c8d2af502.html.

[29] Thibodeau, Patrick. “IT layoffs at insurance firm are a ‘never-ending funeral.’” (May 31, 2016). ComputerWorld. Retrieved from https://www.computerworld.com/article/1670764/it-layoffs-at-insurance-firm-are-a-never-ending-funeral.html.

[30] Hiltzik, Michael. “How the University of California exploited a visa loophole to move tech jobs to India.” Los Angeles Times. (January 6, 2017). Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-uc-visas-20170108-story.html. See also Hanson, Louis. “After pink slips, UCSF workers train their foreign replacements.” (November 2016). The Mercury News. Retrieved from https://www.mercurynews.com/2016/11/03/after-pink-slips-ucsf-tech-workers-train-their-foreign-replacements/.

[31] Hiltzik, Michael. “How the University of California exploited a visa loophole to move tech jobs to India.” [above, n. 30].

[32] “TVA Turns to IT Offshoring Firms, H-1B Workers to Replace TVA IT Workers.” Letter from Paul Shearon and Matthew S. Biggs to Hon. John Barrasso and Hon. Tom Carper. (April 28, 2020). Retrieved from

https://www.ifpte.org/news/tva-turns-to-it-offshoring-firms-h-1b-workers-to-replace-tva-it-workers.

[33] Kruesi, Kimberlee. “TVA rescinds decision to outsource technology jobs.” Federal News Network. (August 7, 2020). Retrieved from https://federalnewsnetwork.com/workforce/2020/08/tva-rescinds-decision-to-outsource-technology-jobs-2/.

[34] See, e.g., Hira, Ron and Daniel Costa. “New evidence of widespread wage theft in the H-1B visa program.” [above, n. 12]; Fan, Eric and Coulter Jones. “Insiders Tell How IT Giant Favored Indian H-1B Workers Over U.S. Employees.” (December 9, 2024). Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2024-cognizant-h1b-visas-discriminates-us-workers/; Hanson, Louis. “After pink slips, UCSF workers train their foreign replacements.” [above, n. 30]; Preston, Julia. “Pink Slips at Disney.” [above, n. 26]; and Kight, Stef W. “U.S. companies are forcing workers to train their own foreign replacements.” [above, n. 28].

[35] See, e.g., Armour, Stephanie. “Workers asked to train foreign replacements.” USA Today. (April 6, 2004). Retrieved from https://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/workplace/2004-04-06-replace_x.htm; and “Immigration Reforms Needed to Protect Skilled American Workers.” Hearing Before the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate. S. HRG. 114–831 (March 17, 2015). Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/114/chrg/CHRG-114shrg47421/CHRG-114shrg47421.pdf.

[36] See, e.g., Ontiveros, Maria L. “H-1B Visas, Outsourcing and Body Shops: A Continuum of Exploitation for High Tech Workers.” Berkeley Journal of Employment and Labor Law 38:1 (2017). Retrieved from https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://lawcat.berkeley.edu/record/1127903/files/fulltext.pdf.

[37] Government Accountability Office. “H-1B Program.” [above, n. 11]. `

[38] Costa, Daniel. “Temporary work visa programs and the need for reform.” Economic Policy Institute. (February 3, 2021). Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/temporary-work-visa-reform/.

[39] Costa, Daniel. “Abuses in the L-Visa Program: Undermining the U.S. Labor Market.” Economic Policy Institute. (August 2010). Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/abuses_in_the_l-visa_program_undermining_the_us_labor_market/.

[40] 8 CFR § 214.2(l)

[41] 8 CFR 214.2(l)(1)(ii)(D)

[42] Ibid.

[43] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “L-1B Intracompany Transferee Specialized Knowledge.” (July 30, 2024). Retrieved from https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/temporary-workers/l-1b-intracompany-transferee-specialized-knowledge.

[44] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “L-1A Intracompany Transferee Executive or Manager.” (July 29, 2024). Retrieved from https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/temporary-workers/l-1a-intracompany-transferee-executive-or-manager.

[45] Costa, Daniel. “Little-known temporary visas for foreign tech workers depress wages.” (November 11, 2014). The Hill. Retrieved from https://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/technology/223607-little-known-temporary-visas-for-foreign-tech-workers-depress.

[46] Costa, Daniel. “Abuses in the L-Visa Program.” [above, n. 39].

[47] Ibid.